Act 1

[This act was omitted in the 1883 revision]

The Forest of Fontainebleau, France in winter

A prelude and chorus of woodcutters and their wives is heard. They complain of their hard life, made worse by war with Spain. Elisabeth, daughter of the King of France, arrives with her attendants. She reassures the people that her impending marriage to Don Carlos, Infante and son of Philip II, King of Spain, will bring the war to an end, and departs.

[This was cut before the Paris première and replaced by a short scene in which Elisabeth crosses the stage and hands out money to the woodcutters; she exits without singing]

Carlos, coming out from hiding, has seen Elisabeth and fallen in love with her (Aria: "Je l'ai vue" / "Io la vidi"). When she reappears, he initially pretends to be a member of the Count of Lerma's delegation. She asks him about Don Carlos, whom she has not yet met. Before long, Carlos reveals his true identity and his feelings, which she reciprocates (Duet: "De quels transports poignants et doux" / "Di quale amor, di quanto ardor"). A cannon-shot signifies that peace has been declared between Spain and France. Thibault appears and gives Elisabeth the surprising news that her hand is to be claimed not by Carlos but by his father, Philip. When Lerma and his followers confirm this, Elisabeth is devastated but feels bound to accept, in order to consolidate the peace. She departs for Spain, leaving Carlos equally devastated.

Act 2

[This is Act 1 in the 1883 revision]

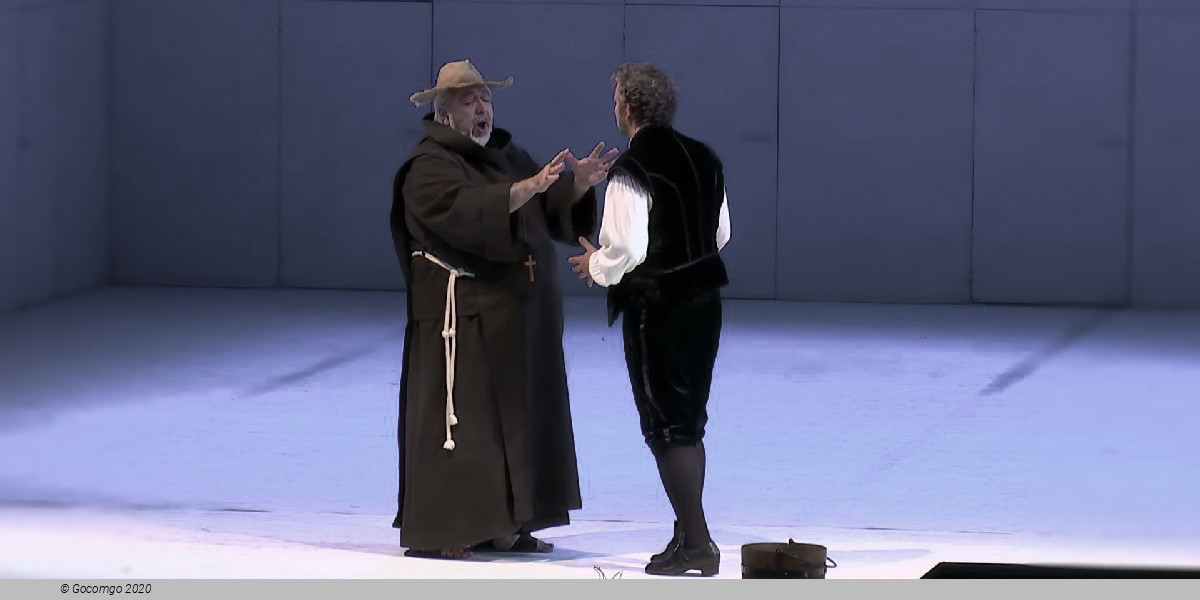

Scene 1: The monastery of Saint-Just (San Jerónimo de Yuste) in Spain

The scene takes place soon after King Philip II and Elisabeth have married. Monks pray before the tomb of the former Emperor Charles V ("Carlo Quinto"). The monks' leader proclaims that the Emperor was proud but has been humbled though error.

Don Carlos enters, anguished that the woman he loves is now his stepmother.

[In the 1883 revision, he sings a revised version of the aria "Je l'ai vue" / "Io la vidi", which was salvaged from the omitted first act but with some different music and different text to reflect his current situation. In the four-act version he already knows that he cannot marry Elisabeth. In the original, when singing the aria, he was still expecting to marry her]

When Carlos pauses in his lament, the leader of the monks proclaims that the turbulence of the world persists even in sacred places; we cannot rest except in Heaven. The sound of his voice frightens Carlos, who thinks it sounds like that of the Emperor Charles V. Carlos further notices that the monk physically resembles the Emperor, and recalls hearing rumors that the Emperor's ghost haunts the monastery.

Carlos' dear friend Rodrigue, Marquis of Posa, who has just arrived from the oppressed land of Flanders, enters. The two greet each other joyfully (Aria: "J'étais en Flandres").

Posa asks for the Infante's aid on behalf of the suffering people there. Carlos reveals that he loves his stepmother. Posa is first shocked, but then sympathetic. He encourages Carlos to leave Spain and go to Flanders, and to forget his pain by focusing on political activity there. The two men swear eternal friendship (Duet: "Dieu, tu semas dans nos âmes" / "Dio, che nell'alma infondere").

King Philip and his new wife, with their attendants, enter also to do homage at Charles V's tomb, while Don Carlos laments his lost love.

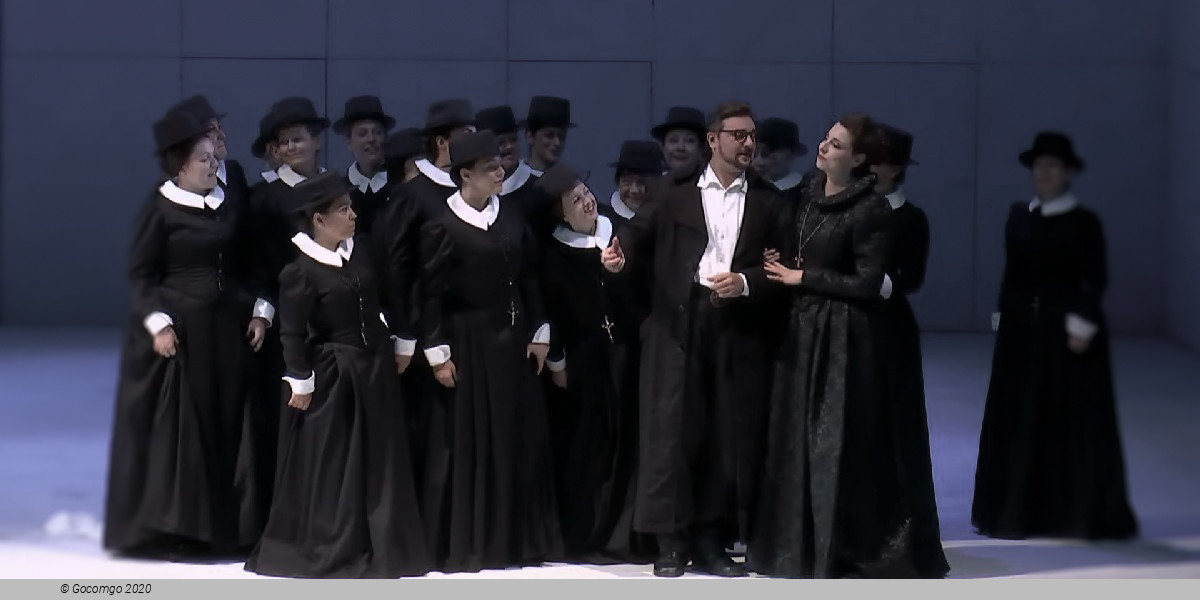

Scene 2: A garden near Saint-Just

Princess Eboli sings the Veil Song ("Au palais des fées" / "Nel giardin del bello") about a Moorish King trying to seduce an alluring veiled beauty, who turns out to be his own neglected wife. Elisabeth enters. Posa gives her a letter from France, which covers a secret note from Don Carlos. At his urging (Aria: "L'Infant Carlos, notre espérance" / "Carlo ch'è sol il nostro amore"), Elisabeth agrees to see the Infante alone. Unaware of this relationship, Eboli infers that she, Eboli, is the one Don Carlos loves.

When they are alone, Don Carlos tells Elisabeth that he is miserable, and asks her to request the King to send him to Flanders. She promptly agrees, provoking Carlos to renew his declarations of love, which she piously rejects. Don Carlos exits in a frenzy, shouting that he must be under a curse. The King enters and becomes angry because the Queen is alone and unattended. His suspicions are insulting to her. He orders the lady-in-waiting who was meant to be attending her, the Countess of Aremberg, to return to France, prompting Elizabeth to sing a sorrowful farewell-aria. (Aria: "Oh ma chère compagne" / "Non pianger, mia compagna").

The King now approaches Posa, with whose character and activism he is impressed, and offers to reward him for his loyalty and service. Posa begs the King to stop oppressing the people of Flanders. The King calls Posa's idealism unrealistic and warns that the Grand Inquisitor is watching him. The King confides in Posa, telling him that he fears that Carlos is having an affair with Elisabeth. Posa replies that Carlos is innocent, and offers to watch Elisabeth and to be responsible for her good behavior. The King gratefully accepts this offer, and again warns Posa to beware of the Grand Inquisitor.

[This dialogue was revised three times by Verdi.]

Act 3

[This is Act 2 in the 1883 revision]

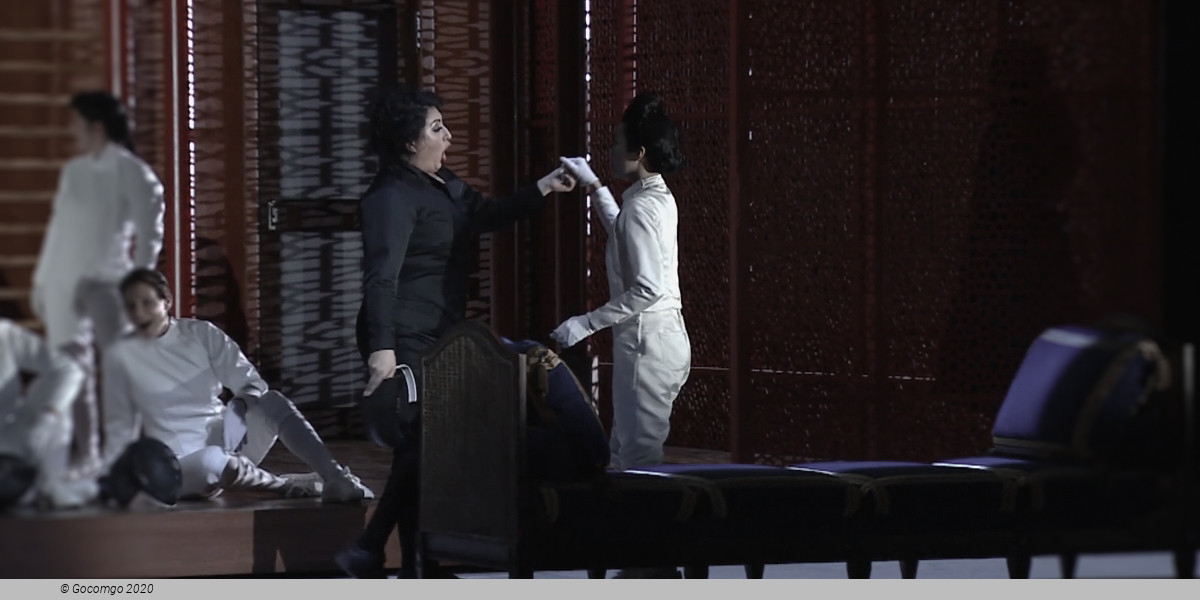

Scene 1: Evening in the Queen's garden in Madrid

Elisabeth is tired, and wishes to concentrate on the following day's coronation of the King. To avoid the divertissement planned for the evening, she exchanges masks with Eboli, assuming that thereby her absence will not be noticed, and leaves.

[This scene was omitted from the 1883 revision]

[In the première, the ballet (choreographed by Lucien Petipa and entitled "La Pérégrina") took place at this point]

At midnight, Don Carlos enters, clutching a note suggesting a tryst in the gardens. Although he thinks this is from Elisabeth, it is really from Eboli. Eboli, who still thinks Don Carlos loves her, enters. Don Carlos mistakes her for Elisabeth in the dark, and passionately declares his love. When he sees Eboli's face, he realizes his error and recoils from her. Eboli guesses his secret - that he was expecting the Queen, whom he loves. She threatens to tell the King that Elisabeth and Carlos are lovers. Carlos, terrified, begs for mercy. Posa enters, and warns her not to cross him; he is the King's confidant. Eboli replies by hinting darkly that she is a formidable and dangerous foe, with power which Posa does not yet know about. (Her power is that she is having an affair with the King, but she does not reveal this yet.) Posa draws his dagger, intending to stab her to death, but reconsiders, spares her, and declares his trust in the Lord. Eboli exits in a vengeful rage. Posa advises Carlos to entrust to him any sensitive, potentially incriminating political documents that he may have and, when Carlos agrees, they reaffirm their friendship.

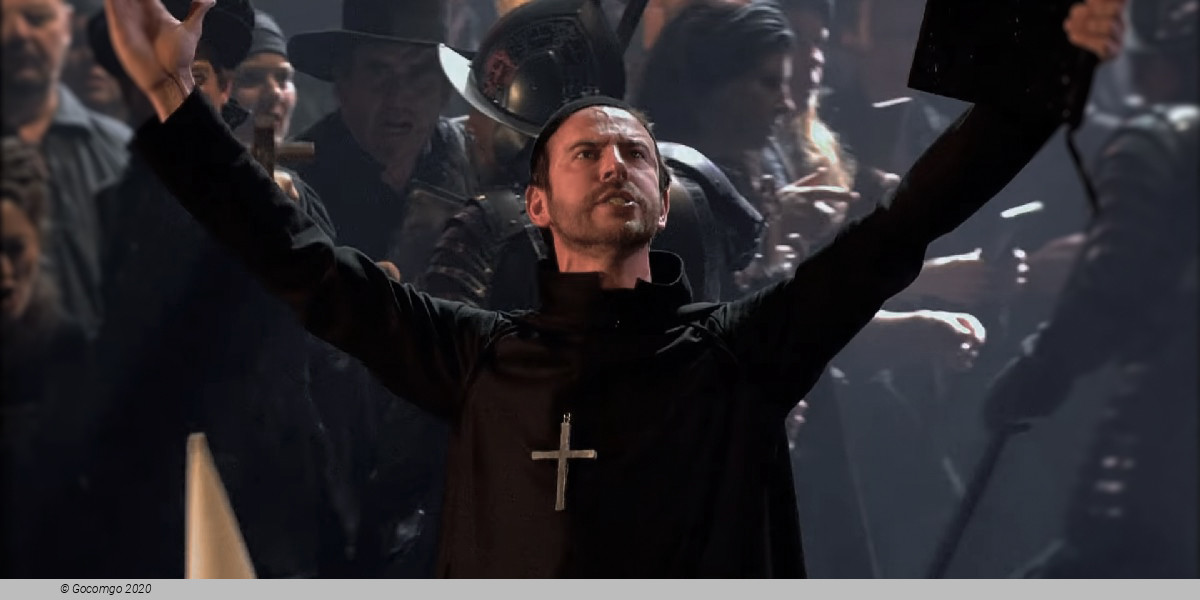

Scene 2: In front of the Cathedral of Valladolid

Preparations are being made for an "Auto-da-fé", the public parade and burning of condemned heretics. While the people celebrate, monks drag the condemned to the woodpile. A royal procession follows, and the King addresses the populace, promising to protect them with fire and sword. Don Carlos enters with six Flemish envoys, who plead with the King for their country's freedom. Although the people and the court are sympathetic, the King, supported by the monks, orders his guards to arrest the envoys. Carlos demands that the King grant him authority to govern Flanders; the King scornfully refuses. Enraged, Carlos draws his sword against the King. The King calls for help but the guards will not attack Don Carlos. Posa steps in and takes the sword from Carlos. Relieved and grateful, the King raises Posa to the rank of Duke. The guards arrest Carlos, the monks fire the woodpile, and as the flames start to rise, a heavenly voice can be heard promising heavenly peace to the condemned souls.

Act 4

[This is Act 3 in the 1883 revision]

Scene 1: Dawn in King Philip's study in Madrid

Alone and suffering from insomnia, the King, in a reverie, laments that Elisabeth has never loved him, that his position means that he has to be eternally vigilant and that he will only sleep properly when he is in his tomb in the Escorial (Aria: "Elle ne m'aime pas" / "Ella giammai m'amò"). The blind, ninety-year-old Grand Inquisitor is announced and shuffles into the King's apartment. When the King asks if the Church will object to him putting his own son to death, the Inquisitor replies that the King will be in good company: God sacrificed His own son. In return for his support, the Inquisitor demands that the King have Posa killed. The King refuses at first to kill his friend, whom he admires and likes. However, the Grand Inquisitor reminds the King that the Inquisition can take down any king; he has created and destroyed other rulers before. Frightened and overwhelmed, the King begs the Grand Inquisitor to forget about the past discussion. The latter replies "Peut-être" / "Forse!" – perhaps! – and leaves. The King bitterly muses on his helplessness to oppose the Church.

Elisabeth enters, alarmed at the apparent theft of her jewel casket. However, the King produces it and points to the portrait of Don Carlos which it contains, accusing her of adultery. She protests her innocence but, when the King threatens her, she faints. In response to his calls for help, into the chamber come Eboli and Posa. Their laments of suspicion cause the King to realize that he has been wrong to suspect his wife ("Maudit soit le soupçon infâme" / "Ah, sii maledetto, sospetto fatale"). Aside, Posa resolves to save Carlos, though it may mean his own death. Eboli feels remorse for betraying Elisabeth; the latter, recovering, expresses her despair.

[This quartet was revised by Verdi in 1883]

Elisabeth and Eboli are left together.

[Duet: "J'ai tout compris", was cut before the première]

Eboli confesses that it was she who told the King that Elisabeth and Carlos were having an affair, for revenge against Carlos for having rejected her. She also confesses that she herself has had an affair with the King. Elisabeth orders her to go into exile, or enter a convent. After Elisabeth exits, Eboli, left alone, curses her own beauty and pride, and resolves to make amends by trying to save Carlos from the Inquisition (Aria: "O don fatal" / "O don fatale").

Scene 2: A prison

Don Carlos has been imprisoned. Posa arrives and tells Carlos that he (Posa) has saved Carlos from being executed, by allowing himself (Posa) to be incriminated by the politically sensitive documents which he had obtained from Carlos earlier (Aria, part 1: "C'est mon jour suprême" / "Per me giunto è il dì supremo"). A shadowy figure appears--one of the Grand Inquisitor's assassins--and shoots Posa in the chest. As he dies, Posa tells Carlos that Elisabeth will meet him at Saint-Just the following day. He adds that he is content to die if his friend can save Flanders and rule over a happier Spain (Aria, part 2: "Ah, je meurs, l'âme joyeuse" / "Io morrò, ma lieto in core"). At that moment, the King enters, offering his son freedom, as Posa had arranged. Carlos repulses him for having murdered Posa. The King sees that Posa is dead and cries out in sorrow.

[Duet: Carlos and the King- "Qui me rendra ce mort ?" /"Chi rende a me quest'uom" It was cut before the première and, following it, Verdi authorized its optional removal. The music was later re-used by Verdi for the Lacrimosa of his Messa da Requiem of 1874]

Bells ring as Elisabeth and Eboli enter. The crowd pushes its way into the prison and threatens the King, demanding the release of Carlos. In the confusion, Eboli escapes with Carlos. The people are brave enough at first in the presence of the King, but they are terrified by the arrival of the Grand Inquisitor, and instantly obey his angry command to quiet down and pay homage to the King.

[After the première, some productions ended this act with the death of Posa. However, in 1883 Verdi provided a much shortened version of the insurrection, as he felt that otherwise it would not be clear how Eboli had fulfilled her promise to rescue Carlos]

Act 5

[This is Act 4 in the 1883 revision]

The moonlit monastery of Yuste

Elisabeth kneels before the tomb of Charles V. She is committed to help Don Carlos on his way to fulfill his destiny in Flanders, but she herself longs only for death (Aria: "Toi qui sus le néant" / "Tu che le vanità"). Carlos appears and tells her that he has overcome his desire for her; he now loves her honorably, as a son loves his mother. They say a final farewell, promising to meet again in Heaven (Duet: "Au revoir dans un monde où la vie est meilleure" / "Ma lassù ci vedremo in un mondo migliore").

[This duet was twice revised by Verdi]

The King and the Grand Inquisitor enter. The King infers that Carlos and Elisabeth have been lovers and demands that they both be immediately killed in a double sacrifice. The Inquisitor confirms that the Inquisition will do its duty. A short summary trial follows, confirming Carlos's putative culpability.

[The trial was omitted in 1883 and does not occur on any recording]

Carlos, calling on God for protection, draws his sword to defend himself against the guards. He is fighting well in spite of being outnumbered, when a mysterious figure (the leader of the monks from the earlier scene at the tomb, which is listed here as Act 2 Scene 1 but is usually the opening scene of the opera, since the first act is usually omitted--so the Monk appears only at the very beginning and the very end of most performances and recordings) suddenly emerges from the tomb of Charles V. He grabs Carlos by the shoulder, and loudly proclaims that the turbulence of the world persists even in the Church; we cannot rest except in Heaven. The King and the Inquisitor recognize the Monk's voice: he is the King's father, Charles V, who was believed dead. Everyone screams in shock and astonishment, while the Monk drags Carlos into the tomb and closes the entrance.

Act 1

This act was omitted in the 1883 revision

The Forest of Fontainebleau, France in winter

A prelude and chorus of woodcutters and their wives is heard. They complain of their hard life, made worse by war with Spain. Elisabeth, daughter of the King of France, arrives with her attendants. She reassures the people that her impending marriage to Don Carlos, Infante and son of Philip II, King of Spain, will bring the war to an end, and departs.

This was cut before the Paris première and replaced by a short scene in which Elisabeth crosses the stage and hands out money to the woodcutters; she exits without singing

Carlos, coming out from hiding, has seen Elisabeth and fallen in love with her (Aria: "Je l'ai vue" / "Io la vidi"). When she reappears, he initially pretends to be a member of the Count of Lerma's delegation. She asks him about Don Carlos, whom she has not yet met. Before long, Carlos reveals his true identity and his feelings, which she reciprocates (Duet: "De quels transports poignants et doux" / "Di quale amor, di quanto ardor"). A cannon-shot signifies that peace has been declared between Spain and France. Thibault appears and gives Elisabeth the surprising news that her hand is to be claimed not by Carlos but by his father, Philip. When Lerma and his followers confirm this, Elisabeth is devastated but feels bound to accept, in order to consolidate the peace. She departs for Spain, leaving Carlos equally devastated.

Act 2

This is Act 1 in the 1883 revision

Scene 1: The monastery of Saint-Just (San Jerónimo de Yuste) in Spain

The scene takes place soon after King Philip II and Elisabeth have married. Monks pray before the tomb of the former Emperor Charles V ("Carlo Quinto"). The monks' leader proclaims that the Emperor was proud but has been humbled though error.

Don Carlos enters, anguished that the woman he loves is now his stepmother.

[In the 1883 revision, he sings a revised version of the aria "Je l'ai vue" / "Io la vidi", which was salvaged from the omitted first act but with some different music and different text to reflect his current situation. In the four-act version he already knows that he cannot marry Elisabeth. In the original, when singing the aria, he was still expecting to marry her]

When Carlos pauses in his lament, the leader of the monks proclaims that the turbulence of the world persists even in sacred places; we cannot rest except in Heaven. The sound of his voice frightens Carlos, who thinks it sounds like that of the Emperor Charles V. Carlos further notices that the monk physically resembles the Emperor, and recalls hearing rumors that the Emperor's ghost haunts the monastery.

Carlos' dear friend Rodrigue, Marquis of Posa, who has just arrived from the oppressed land of Flanders, enters. The two greet each other joyfully (Aria: "J'étais en Flandres").

Posa asks for the Infante's aid on behalf of the suffering people there. Carlos reveals that he loves his stepmother. Posa is first shocked, but then sympathetic. He encourages Carlos to leave Spain and go to Flanders, and to forget his pain by focusing on political activity there. The two men swear eternal friendship (Duet: "Dieu, tu semas dans nos âmes" / "Dio, che nell'alma infondere").

King Philip and his new wife, with their attendants, enter also to do homage at Charles V's tomb, while Don Carlos laments his lost love.

Scene 2: A garden near Saint-Just

Princess Eboli sings the Veil Song ("Au palais des fées" / "Nel giardin del bello") about a Moorish King trying to seduce an alluring veiled beauty, who turns out to be his own neglected wife. Elisabeth enters. Posa gives her a letter from France, which covers a secret note from Don Carlos. At his urging (Aria: "L'Infant Carlos, notre espérance" / "Carlo ch'è sol il nostro amore"), Elisabeth agrees to see the Infante alone. Unaware of this relationship, Eboli infers that she, Eboli, is the one Don Carlos loves.

When they are alone, Don Carlos tells Elisabeth that he is miserable, and asks her to request the King to send him to Flanders. She promptly agrees, provoking Carlos to renew his declarations of love, which she piously rejects. Don Carlos exits in a frenzy, shouting that he must be under a curse. The King enters and becomes angry because the Queen is alone and unattended. His suspicions are insulting to her. He orders the lady-in-waiting who was meant to be attending her, the Countess of Aremberg, to return to France, prompting Elizabeth to sing a sorrowful farewell-aria. (Aria: "Oh ma chère compagne" / "Non pianger, mia compagna").

The King now approaches Posa, with whose character and activism he is impressed, and offers to reward him for his loyalty and service. Posa begs the King to stop oppressing the people of Flanders. The King calls Posa's idealism unrealistic and warns that the Grand Inquisitor is watching him. The King confides in Posa, telling him that he fears that Carlos is having an affair with Elisabeth. Posa replies that Carlos is innocent, and offers to watch Elisabeth and to be responsible for her good behavior. The King gratefully accepts this offer, and again warns Posa to beware of the Grand Inquisitor.

This dialogue was revised three times by Verdi.

Act 3

This is Act 2 in the 1883 revision

Scene 1: Evening in the Queen's garden in Madrid

Elisabeth is tired, and wishes to concentrate on the following day's coronation of the King. To avoid the divertissement planned for the evening, she exchanges masks with Eboli, assuming that thereby her absence will not be noticed, and leaves.

This scene was omitted from the 1883 revision

At midnight, Don Carlos enters, clutching a note suggesting a tryst in the gardens. Although he thinks this is from Elisabeth, it is really from Eboli. Eboli, who still thinks Don Carlos loves her, enters. Don Carlos mistakes her for Elisabeth in the dark, and passionately declares his love. When he sees Eboli's face, he realizes his error and recoils from her. Eboli guesses his secret - that he was expecting the Queen, whom he loves. She threatens to tell the King that Elisabeth and Carlos are lovers. Carlos, terrified, begs for mercy. Posa enters, and warns her not to cross him; he is the King's confidant. Eboli replies by hinting darkly that she is a formidable and dangerous foe, with power which Posa does not yet know about. (Her power is that she is having an affair with the King, but she does not reveal this yet.) Posa draws his dagger, intending to stab her to death, but reconsiders, spares her, and declares his trust in the Lord. Eboli exits in a vengeful rage. Posa advises Carlos to entrust to him any sensitive, potentially incriminating political documents that he may have and, when Carlos agrees, they reaffirm their friendship.

Scene 2: In front of the Cathedral of Valladolid

Preparations are being made for an "Auto-da-fé", the public parade and burning of condemned heretics. While the people celebrate, monks drag the condemned to the woodpile. A royal procession follows, and the King addresses the populace, promising to protect them with fire and sword. Don Carlos enters with six Flemish envoys, who plead with the King for their country's freedom. Although the people and the court are sympathetic, the King, supported by the monks, orders his guards to arrest the envoys. Carlos demands that the King grant him authority to govern Flanders; the King scornfully refuses. Enraged, Carlos draws his sword against the King. The King calls for help but the guards will not attack Don Carlos. Posa realizes that actually attacking the King would be disastrous for Carlos. He steps forward and defuses the situation by taking Carlos' sword from him. Carlos, astonished, yields to his friend without resisting. Relieved and grateful, the King raises Posa to the rank of Duke. The guards arrest Carlos, the monks fire the woodpile, and as the flames start to rise, a heavenly voice can be heard promising heavenly peace to the condemned souls.

Act 4

This is Act 3 in the 1883 revision

Scene 1: Dawn in King Philip's study in Madrid

Alone and suffering from insomnia, the King, in a reverie, laments that Elisabeth has never loved him, that his position means that he has to be eternally vigilant and that he will only sleep properly when he is in his tomb in the Escorial (Aria: "Elle ne m'aime pas" / "Ella giammai m'amò"). The blind, ninety-year-old Grand Inquisitor is announced and shuffles into the King's apartment. When the King asks if the Church will object to him putting his own son to death, the Inquisitor replies that the King will be in good company: God sacrificed His own son. In return for his support, the Inquisitor demands that the King have Posa killed. The King refuses at first to kill his friend, whom he admires and likes. However, the Grand Inquisitor reminds the King that the Inquisition can take down any king; he has created and destroyed other rulers before. Frightened and overwhelmed, the King begs the Grand Inquisitor to forget about the past discussion. The latter replies "Peut-être" / "Forse!" – perhaps! – and leaves. The King bitterly muses on his helplessness to oppose the Church.

Elisabeth enters, alarmed at the apparent theft of her jewel casket. However, the King produces it and points to the portrait of Don Carlos which it contains, accusing her of adultery. She protests her innocence but, when the King threatens her, she faints. In response to his calls for help, into the chamber come Eboli and Posa. Their laments of suspicion cause the King to realize that he has been wrong to suspect his wife ("Maudit soit le soupçon infâme" / "Ah, sii maledetto, sospetto fatale"). Aside, Posa resolves to save Carlos, though it may mean his own death. Eboli feels remorse for betraying Elisabeth; the latter, recovering, expresses her despair.

This quartet was revised by Verdi in 1883

Elisabeth and Eboli are left together.

Duet: "J'ai tout compris", was cut before the première

Eboli confesses that it was she who told the King that Elisabeth and Carlos were having an affair, for revenge against Carlos for having rejected her. She also confesses that she herself has had an affair with the King. Elisabeth orders her to go into exile, or enter a convent. After Elisabeth exits, Eboli, left alone, curses her own beauty and pride, and resolves to make amends by trying to save Carlos from the Inquisition (Aria: "O don fatal" / "O don fatale").

Scene 2: A prison

Baril Gédéon, "Il Maestro Verdi", cartoon by Le Hanneron, 14 March 1867. (Museum of the Paris Opera)

Don Carlos has been imprisoned. Posa arrives and tells Carlos that he (Posa) has saved Carlos from being executed, by allowing himself (Posa) to be incriminated by the politically sensitive documents which he had obtained from Carlos earlier (Aria, part 1: "C'est mon jour suprême" / "Per me giunto è il dì supremo"). A shadowy figure appears--one of the Grand Inquisitor's assassins--and shoots Posa in the chest. As he dies, Posa tells Carlos that Elisabeth will meet him at Saint-Just the following day. He adds that he is content to die if his friend can save Flanders and rule over a happier Spain (Aria, part 2: "Ah, je meurs, l'âme joyeuse" / "Io morrò, ma lieto in core"). At that moment, the King enters, offering his son freedom, as Posa had arranged. Carlos repulses him for having murdered Posa. The King sees that Posa is dead and cries out in sorrow.

Duet: Carlos and the King- "Qui me rendra ce mort ?" /"Chi rende a me quest'uom" It was cut before the première and, following it, Verdi authorized its optional removal. The music was later re-used by Verdi for the Lacrimosa of his Messa da Requiem of 1874

Bells ring as Elisabeth and Eboli enter. The crowd pushes its way into the prison and threatens the King, demanding the release of Carlos. In the confusion, Eboli escapes with Carlos. The people are brave enough at first in the presence of the King, but they are terrified by the arrival of the Grand Inquisitor, and instantly obey his angry command to quiet down and pay homage to the King.

After the première, some productions ended this act with the death of Posa. However, in 1883 Verdi provided a much shortened version of the insurrection, as he felt that otherwise it would not be clear how Eboli had fulfilled her promise to rescue Carlos

Act 5

This is Act 4 in the 1883 revision

The moonlit monastery of Yuste

Elisabeth kneels before the tomb of Charles V. She is committed to help Don Carlos on his way to fulfill his destiny in Flanders, but she herself longs only for death (Aria: "Toi qui sus le néant" / "Tu che le vanità"). Carlos appears and tells her that he has overcome his desire for her; he now loves her honorably, as a son loves his mother. They say a final farewell, promising to meet again in Heaven (Duet: "Au revoir dans un monde où la vie est meilleure" / "Ma lassù ci vedremo in un mondo migliore").

This duet was twice revised by Verdi

The King and the Grand Inquisitor enter, with several armed guards. The King infers that Carlos and Elisabeth have been lovers and demands that they both be immediately killed in a double sacrifice. The Inquisitor confirms that the Inquisition will do its duty. A short summary trial follows, confirming Carlos's putative culpability.

The trial was omitted in 1883 and does not occur on any recording

Carlos, calling on God for protection, draws his sword to defend himself against the guards. He is fighting well in spite of being outnumbered, when a mysterious figure (the leader of the monks from the earlier scene at the tomb, which is listed here as Act 2 Scene 1 but is usually the opening scene of the opera, since the first act is usually omitted--so the Monk appears only at the very beginning and the very end of most performances and recordings) suddenly emerges from the tomb of Charles V. He grabs Carlos by the shoulder, and loudly proclaims that the turbulence of the world persists even in the Church; we cannot rest except in Heaven. The King and the Inquisitor recognize the Monk's voice: he is the King's father, Charles V, who was believed dead. Everyone screams in shock and astonishment, while the Monk drags Carlos into the tomb and closes the entrance.

Palais Garnier: Place de l’Opéra, 75009 Paris; Opéra Bastille: Place de la Bastille, 75012 Paris

Palais Garnier: Place de l’Opéra, 75009 Paris; Opéra Bastille: Place de la Bastille, 75012 Paris