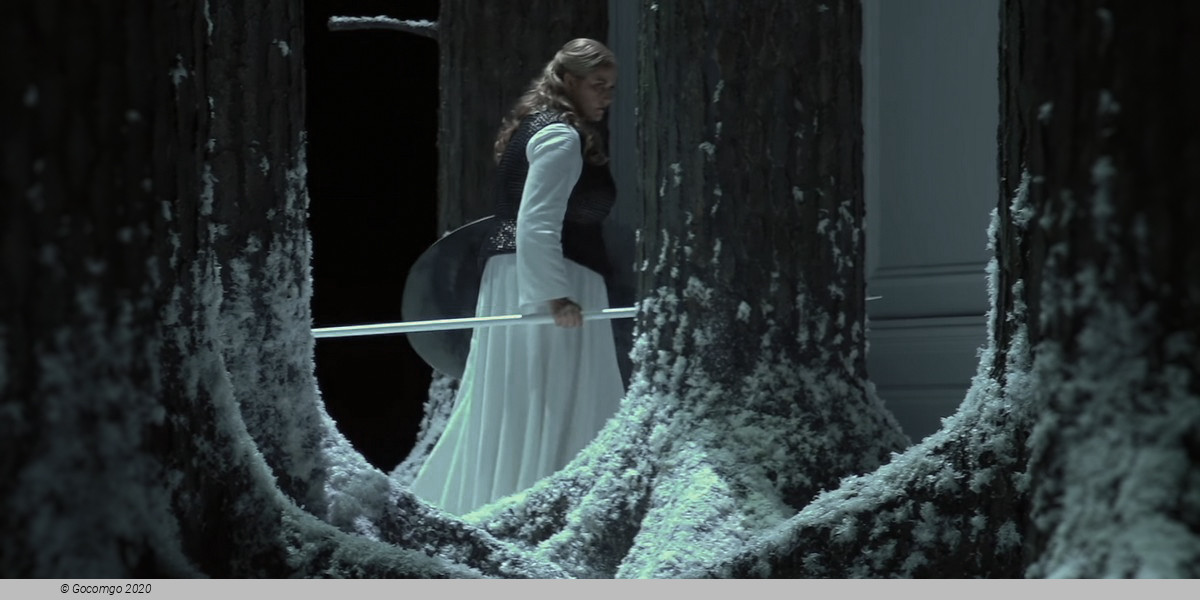

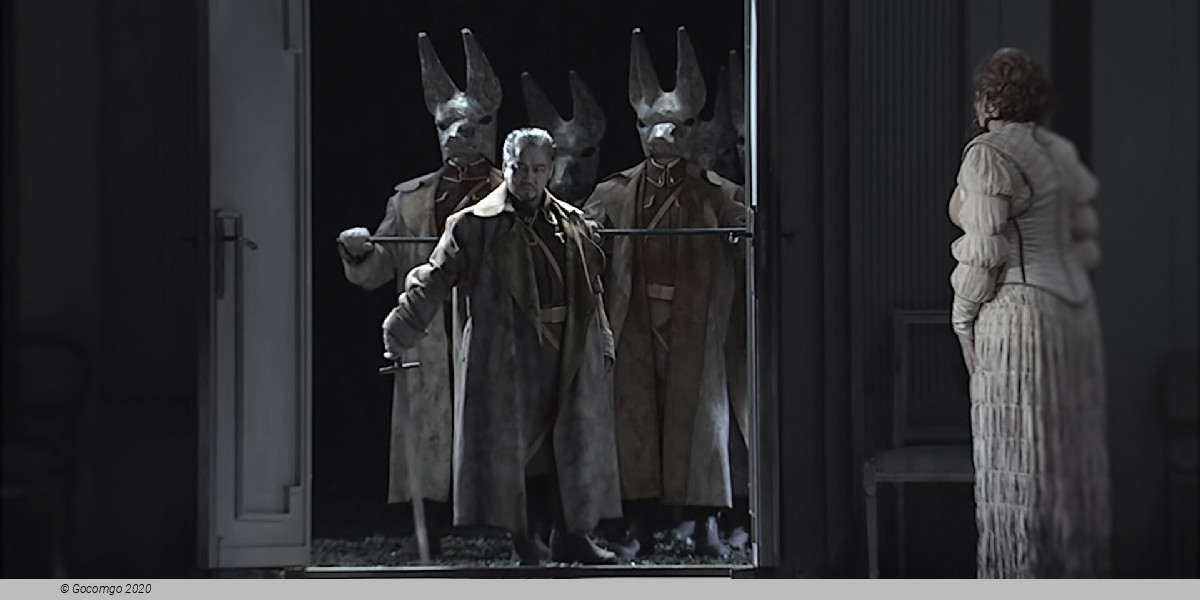

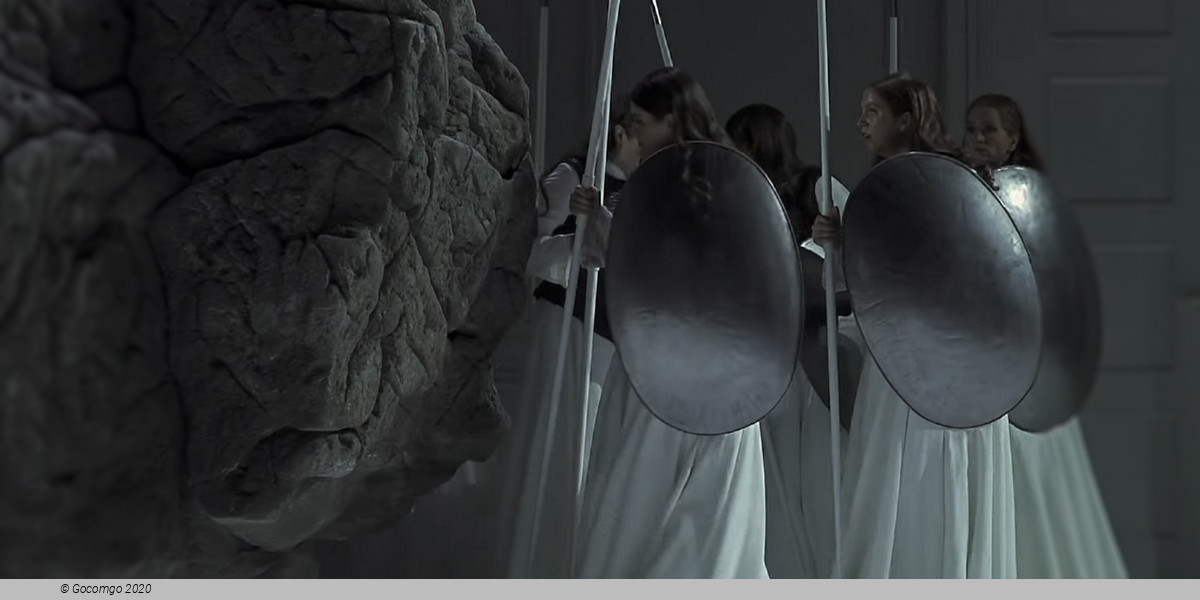

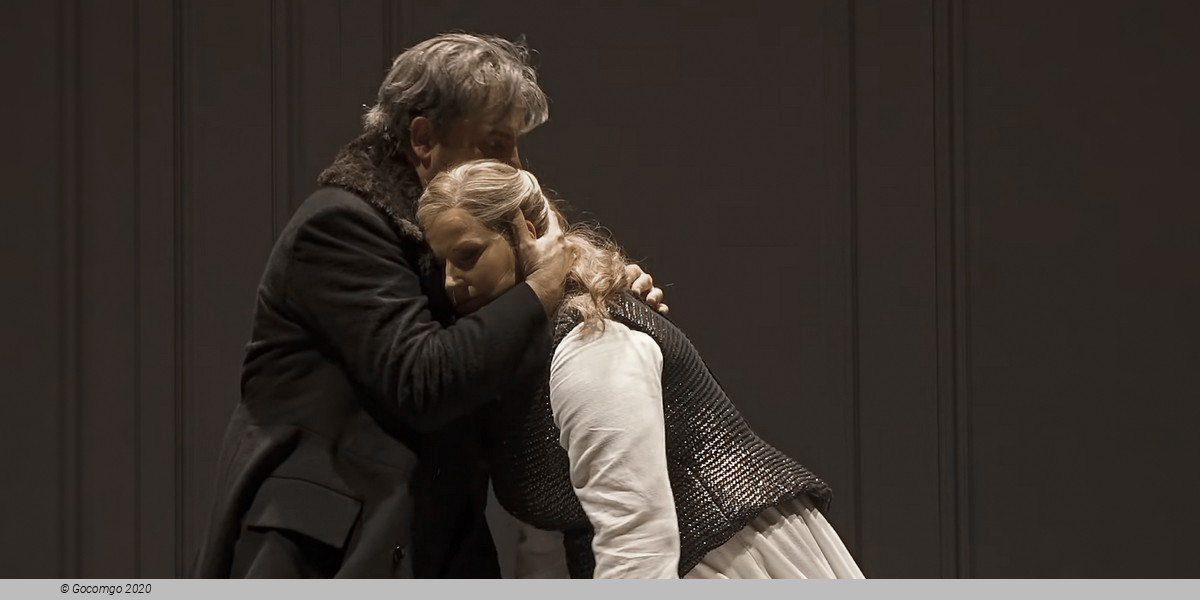

CONFLICT BETWEEN POWER AND LOVE

Die Walküre remains unsurpassed in its portrayal of the fatal conflict between power and love, the overarching theme of the Ring des Nibelungen. Composed as the first day of Wagner’s ‘Buhnenfestspiel’, Die Walküre takes a giant leap from the prologue, Das Rheingold, into the thick of the action.

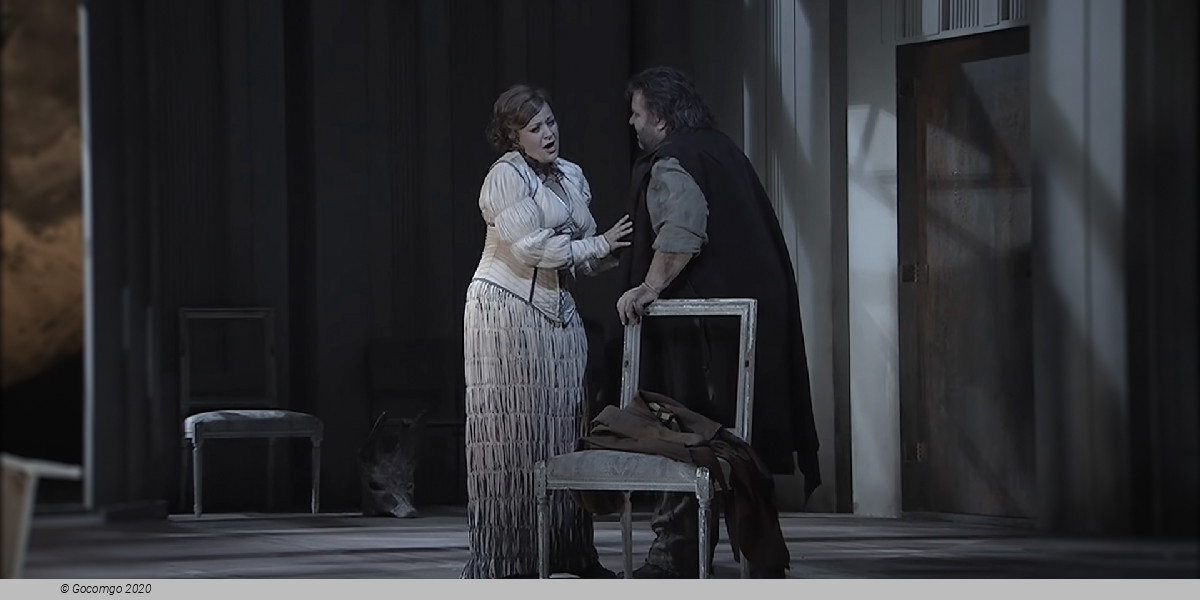

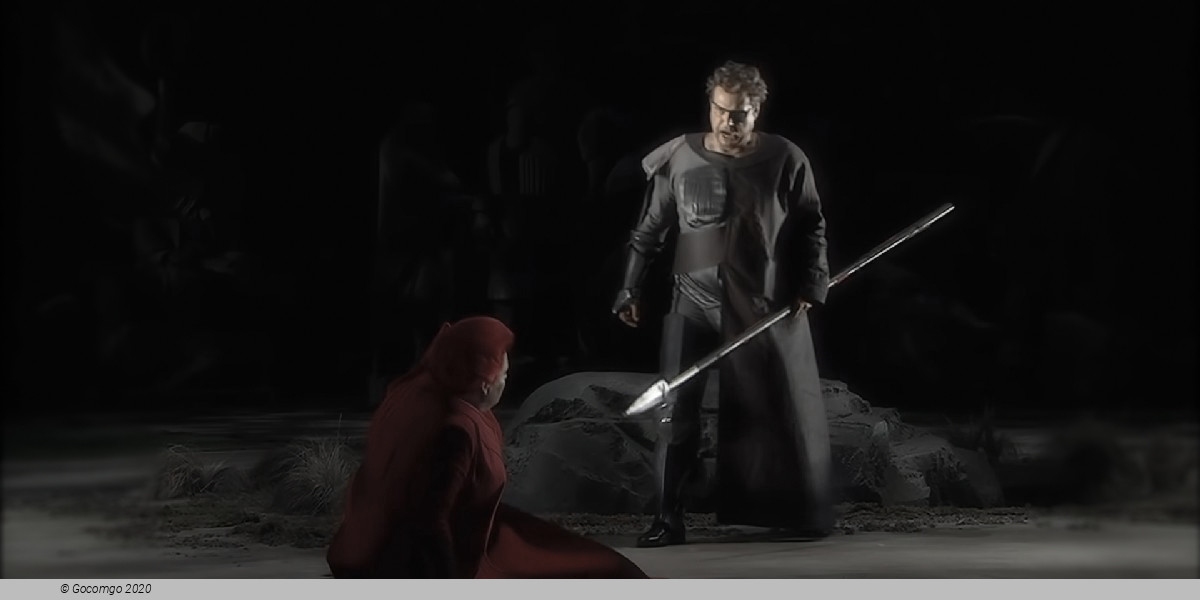

GODS WITH HUMAN DESIRES

A compelling drama enacted by relatable characters, thrilling music and fiery spectacle, Die Walküre forms the ‘human’ heart of Wagner’s mythical four-part cycle, in which the gods reveal their human desires. The doomed romance between Wotan’s bastards Sieglinde and Siegmund is sealed and Wotan’s Valkyrie daughter Brünnhilde is punished for attempting to aid the lovers. Stripped of her divine status and immortality, Brünhilde sleeps in a circle of fire to await a hero’s kiss.

ADVENTURE SEATS

Adventurous, no fear of heights and a desire to experience Die Walküre in an unusual way? Then take a seat on the adventure seats. These seats float above the stage and offer a unique perspective on the opera.

Please mind that there is no view of the surtitles from the adventure seats.

Völsunga saga

The Völsunga saga (often referred to in English as the Volsunga Saga or Saga of the Völsungs) is a legendary saga, a late 13th century poetic rendition in the Icelandic language of the origin and decline of the Völsung clan (including the story of Sigurd and Brynhild and destruction of the Burgundians).

The saga covers themes including the power struggles among Sigurd's ancestors; Sigurd's killing of the dragon Fafnir; and the influence of the cursed ring Andvaranaut.

The saga has given rise to operatic and literary adaptations including Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, Henrik Ibsen's The Vikings at Helgeland, William Morris's The Story of Sigurd the Volsung and the Fall of the Niblungs, and J. R. R. Tolkien's The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún.

Poetic Edda

Poetic Edda is the modern attribution for an unnamed collection of Old Norse anonymous poems, which is different from the Edda written by Snorri Sturluson. Several versions exist, all primarily of text from the Icelandic medieval manuscript known as the Codex Regius. The Codex Regius is arguably the most important extant source on Norse mythology and Germanic heroic legends. From the early 19th century onwards, it has had a powerful influence on later Scandinavian literatures. Not only by its stories, but also by the visionary force and the dramatic quality of many of the poems. It has also become an inspiring model for many later innovations in poetic meter, particularly in Nordic languages, offering many varied examples of terse, stress-based metrical schemes that lack any final rhyme by instead using alliterative devices and strongly-concentrated imagery. Poets who have acknowledged their debt to the Codex Regius include Vilhelm Ekelund, August Strindberg, J. R. R. Tolkien, Ezra Pound, Jorge Luis Borges, and Karin Boye.

Codex Regius was written during the 13th century, but nothing was known of its whereabouts until 1643, when it came into the possession of Brynjólfur Sveinsson, then Bishop of Skálholt. At the time, versions of the Edda were known in Iceland, but scholars speculated that there once was another Edda, an Elder Edda, which contained the pagan poems that Snorri quotes in his Edda. When Codex Regius was discovered, it seemed that the speculation had proved, but modern scholarly research has shown that Edda was likely written first and the two were, at most, connected by a common source.

Brynjólfur attributed the manuscript to Sæmundr the Learned, a larger-than-life 12th century Icelandic priest. That attribution is rejected by modern scholars, but the name Sæmundar Edda is still sometimes associated with both the "Codex Regius" and versions of "Poetic Edda" using it as a source.

Bishop Brynjólfur sent Codex Regius as a present to the Danish king, which gave the name. For centuries, it was stored in the Royal Library in Copenhagen but in 1971, it was returned to Iceland.

Prose Edda

The Prose Edda, also known as the Younger Edda, Snorri's Edda (Icelandic: Snorra Edda) or, historically, simply as Edda, is an Old Norse work of literature written in Iceland during the early 13th century. The work is often assumed to have been written, or at least compiled, by the Icelandic scholar, lawspeaker, and historian Snorri Sturluson c. 1220.

It begins with a euhemerized Prologue, a section on the Norse cosmogony, pantheon, and myths. This is followed by three distinct books: Gylfaginning (consisting of around 20,000 words), Skáldskaparmál (around 50,000 words) and Háttatal (around 20,000 words). Seven manuscripts, dating from around 1300 to around 1600, have independent textual value. Sturluson planned the collection as a textbook. It was to enable Icelandic poets and readers to understand the subtleties of alliterative verse, and to grasp the meaning behind the many kenningar (compounds) that were used in skaldic poetry.

The Prose Edda was originally referred to as simply Edda, but was later titled the Prose Edda in modern collections to distinguish it from the collections titled Poetic Edda that are largely based on Codex Regius, a collection of poetry composed after Edda in 13th century Iceland. At that time, versions of the Edda were well known in Iceland, but scholars speculated that there once was an Elder Edda which contained the poems which Snorri quotes in his Edda.

Nibelungenlied

The Nibelungenlied (Middle High German: Der Nibelunge liet or Der Nibelunge nôt), translated as The Song of the Nibelungs, is an epic poem from around 1200 written in Middle High German. Its anonymous poet was likely from the region of Passau. The Nibelungenlied is based on an oral tradition that has some of its origin in historic events and individuals of the 5th and 6th centuries and that spread throughout almost all of Germanic-speaking Europe. Parallels to the German poem from Scandinavia are found especially in the heroic lays of the Poetic Edda and in the Völsunga saga.

The poem is split into two parts: in the first part, Siegfried comes to Worms to acquire the hand of the Burgundian princess Kriemhild from her brother King Gunther. Gunther agrees to let Siegfried marry Kriemhild if Siegfried helps Gunther acquire the warrior-queen Brünhild as his wife. Siegfried does this and marries Kriemhild; however Brünhild and Kriemhild become rivals, leading eventually to Siegfried's murder by the Burgundian vassal Hagen with Gunther's involvement. In the second part, the widow Kriemhild is married to Etzel, king of the Huns. She later invites her brother and his court to visit Etzel's kingdom intending to kill Hagen. Her revenge results in the death of all the Burgundians who came to Etzel's court as well as the destruction of Etzel's kingdom and the death of Kriemhild herself.

The Nibelungenlied was the first heroic epic put into writing in Germany, helping to found a larger genre of written heroic poetry. The poem's tragedy appears to have bothered its medieval audience, and very early on a sequel was written, the Nibelungenklage, which made the tragedy less final. The poem was forgotten after around 1500, but was rediscovered in 1755. Dubbed the "German Iliad", the Nibelungenlied began a new life as the German national epic. The poem was appropriated for nationalist purposes and was heavily used in anti-democratic, reactionary, and National-Socialist propaganda before and during the Second World War. Its legacy today is most visible in Richard Wagner's operatic cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, which, however, is mostly based on Old Norse sources. In 2009, the three main manuscripts of the Nibelungenlied were inscribed in UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in recognition of their historical significance. It has been called "one of the most impressive, and certainly the most powerful, of the German epics of the Middle Ages."

Völsunga saga

Two of the main themes of the saga are the male responsibility of rewarding friends and punishing acts of shame, and the female responsibility of goading for revenge.[citation needed] Together these create much of the contention in the saga.

It is largely based on epic poetry of the historic Elder Edda. The earliest known pictorial representation of this tradition is the Ramsund carving, Sweden, which was created c. 1000 AD.

The origins of the material are considerably older, however, and it in part echoes real events in Central Europe during the Migration Period, chiefly the destruction of the Kingdom of the Burgundians by the Huns in the fifth century. Some of the poems contained in the Elder Edda relate episodes from the Völsung legend. On the other hand, the only surviving medieval manuscript of the saga, Ny kgl. Saml. 1824 b 4to, which is held by the Royal Library of Denmark, dates to about 1400. In this manuscript, the saga leads straight in to Ragnars saga loðbrókar.

Poetic Edda

The Eddic poems are composed in alliterative verse. Most are in fornyrðislag, while málaháttr is a common variation. The rest, about a quarter, are composed in ljóðaháttr. The language of the poems is usually clear and relatively unadorned. Kennings are often employed, though they do not arise as frequently, nor are they as complex, as those found in skaldic poetry.

Authorship

Like most early poetry, the Eddic poems were minstrel poems, passed orally from singer to singer and from poet to poet for centuries. None of the poems are attributed to a particular author, though many of them show strong individual characteristics and are likely to have been the work of individual poets. While scholars have speculated on hypothetical authors, firm and accepted conclusions have never been reached.

Date

The dating of the poems has been a source of lively scholarly argument for a long time, and firm conclusions are hard to reach. Lines from the Eddic poems sometimes appear in poems by known poets, but such evidence is difficult to evaluate. For example, Eyvindr skáldaspillir composed in the latter half of the 10th century, and he uses a couple of lines in his Hákonarmál which are also found in Hávamál. It is possible that he was quoting a known poem, but it is also possible that Hávamál, or at least the strophe in question, is the younger derivative work.

The few demonstrably historical characters mentioned in the poems, such as Attila, provide a terminus post quem of sorts. The dating of the manuscripts themselves provides a more useful terminus ante quem.

Individual poems have individual clues to their age. For example, Atlamál hin groenlenzku is claimed by its title to have been composed in Greenland, and seems so by some internal evidence. If so, it can be no earlier than about 985, since there were no Scandinavians in Greenland until that time.

In some cases, old poems may have been interpolated with younger verses or merged with other poems. For example, stanzas 9-16 of Völuspá, the "Dvergatal" or "Roster of Dwarfs", is considered by some scholars to be an interpolation.

Location

The problem of dating the poems is linked with the problem of determining where they were composed. Iceland was not settled until approximately 870, so anything composed before that time would necessarily have been elsewhere, most likely in Scandinavia. More recent poems, on the other hand, are likely Icelandic in origin.

Scholars have attempted to localize individual poems by studying the geography, flora, and fauna to which they refer. This approach usually does not yield firm results. For example, there are no wolves in Iceland, but we can be sure that Icelandic poets were familiar with the species. Similarly, the apocalyptic descriptions of Völuspá have been taken as evidence that the poet who composed it had seen a volcanic eruption in Iceland - but this is hardly certain.

Prose Edda

Prologue

Main article: Prologue (Prose Edda)

The Prologue is the first section of four books of the Edda, consisting of an euhemerized Christian account of the origins of Nordic mythology: the Nordic gods are described as human Trojan warriors who left Troy after the fall of that city (an origin similar to the one chosen by Geoffrey of Monmouth in the 12th century to account for the ancestry of the British nation, and which parallels Virgil's Aeneid). According to Edda, these warriors settled in northern Europe, where they were accepted as divine kings because of their superior culture and technology. Remembrance ceremonies later conducted at their burial sites degenerate into heathen cults, turning them into gods. Alexander M. Bruce suggested that Sturlson was in possession of the Langfeðgatal or a closely related text when he composed the detailed list of gods and heroes given. He noted parallel sequences in the Langfeðgatal and the Edda, noting the second appearance of a "Scyld figure" as both an ancestor and a descendant of Odin in both. This figure is expanded upon in the Edda detailing Skjöldr as Odin's son after his migration northwards to Reidgothland and his ordination as a King of Denmark.

Gylfaginning

Main article: Gylfaginning

Gylfaginning (Old Icelandic "the tricking of Gylfi") follows the Prologue in Edda. Gylfaginning deals with the creation and destruction of the world of the Nordic gods, and many other aspects of Norse mythology. The section is written in prose interspersed with quotes from skaldic poetry.

Skáldskaparmál

Main article: Skáldskaparmál

Skáldskaparmál (Old Icelandic "the language of poetry") is the third section of Edda, and consists of a dialogue between Ægir, a god associated with the sea, and Bragi, a skaldic god, in which both Nordic mythology and discourse on the nature of poetry are intertwined. The origin of a number of kenningar are given and Bragi then delivers a systematic list of kenningar for various people, places, and things. Bragi then goes on to discuss poetic language in some detail, in particular heiti, the concept of poetical words which are non-periphrastic, for example "steed" for "horse", and again systematises these.

Háttatal

Main article: Háttatal

Háttatal (Old Icelandic "list of verse-forms") is the last section of Edda. The section is composed by the Icelandic poet, politician, and historian Snorri Sturluson. Primarily using his own compositions, it exemplifies the types of verse forms used in Old Norse poetry. Snorri took a prescriptive as well as descriptive approach; he has systematized the material, often noting that "the older poets did not always" follow his rules.

Nibelungenlied

The poem in its various written forms was lost by the end of the 16th century, but manuscripts from as early as the 13th century were re-discovered during the 18th century. There are thirty-seven known manuscripts of the Nibelungenlied and its variant versions. Eleven of these manuscripts are essentially complete. The oldest version seems to be the one preserved in manuscript "B". Twenty-four manuscripts are in various fragmentary states of completion, including one version in Dutch (manuscript 'T').

The text contains approximately 2,400 stanzas in 39 Aventiuren. The title under which the poem has been known since its discovery is derived from the final line of one of the three main versions, "hie hât daz mære ein ende: daz ist der Nibelunge liet" ("here the story takes an end: this is the lay of the Nibelungs"). Liet here means lay, tale or epic rather than simply song, as it would in Modern German.

The manuscripts' sources deviate considerably from one another. Philologists and literary scholars usually designate three main genealogical groups for the entire range of available manuscripts, with two primary versions comprising the oldest known copies: *AB and *C. This categorization derives from the signatures on the *A, *B, and *C manuscripts as well as the wording of the last verse in each source: "daz ist der Nibelunge liet" or "daz ist der Nibelunge nôt". Nineteenth-century philologist Karl Lachmann developed this categorisation of the manuscript sources in Der Nibelunge Noth und die Klage nach der ältesten Überlieferung mit Bezeichnung des Unechten und mit den Abweichungen der gemeinen Lesart (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1826).

Amstel 3

Amstel 3