A striking display of the myriad creative possibilities inspired by Stravinsky’s body of work

A smorgasbord of works from the Company’s founding choreographers highlights the creative possibility of Stravinsky’s multifaceted output. Set to Stravinsky’s symphonic suite of the same name, Balanchine’s plotless Divertimento from ‘Le Baiser de la Fée’ conveys a sense of both playfulness and foreboding with its fleet choreography. Inspired by the Concerto in D for String Orchestra’s dramatic intensity, Robbins crafted The Cage, a boundary-breaking tale of the violent actions of a “Novice” in a female-centric, cult-like hive of insects. Balanchine’s admiration for Stravinsky’s music finds its ultimate expression in Duo Concertant, in which the leotard-clad couple shares the stage with the violin and piano, and in Rubies, a dazzling work set to Stravinsky’s jazzy Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra.

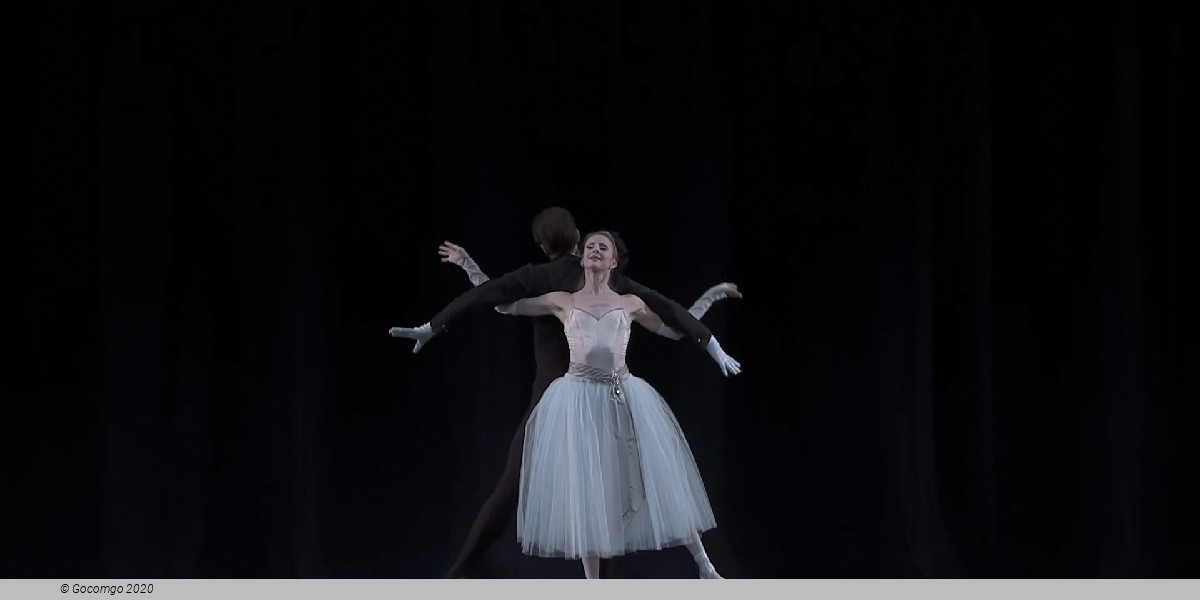

An abstraction of a Hans Christian Andersen fairytale, Stravinsky’s colorfully playful yet foreboding divertimento sets the stage for Balanchine’s fleet-footed choreography.

In 1937 Balanchine choreographed the full-length ballet for his American Ballet at the Metropolitan Opera House entitled The Fairy’s Kiss (also known as Le Baiser de la Fée), and set to Stravinsky’s score. For the 1972 Stravinsky Festival Balanchine created an entirely new work that used excerpts from the concert suite Stravinsky created in 1934. In 1974 Balanchine added a final movement to the ballet which is the version performed today as Divertimento from 'Le Baiser de la Fée.'

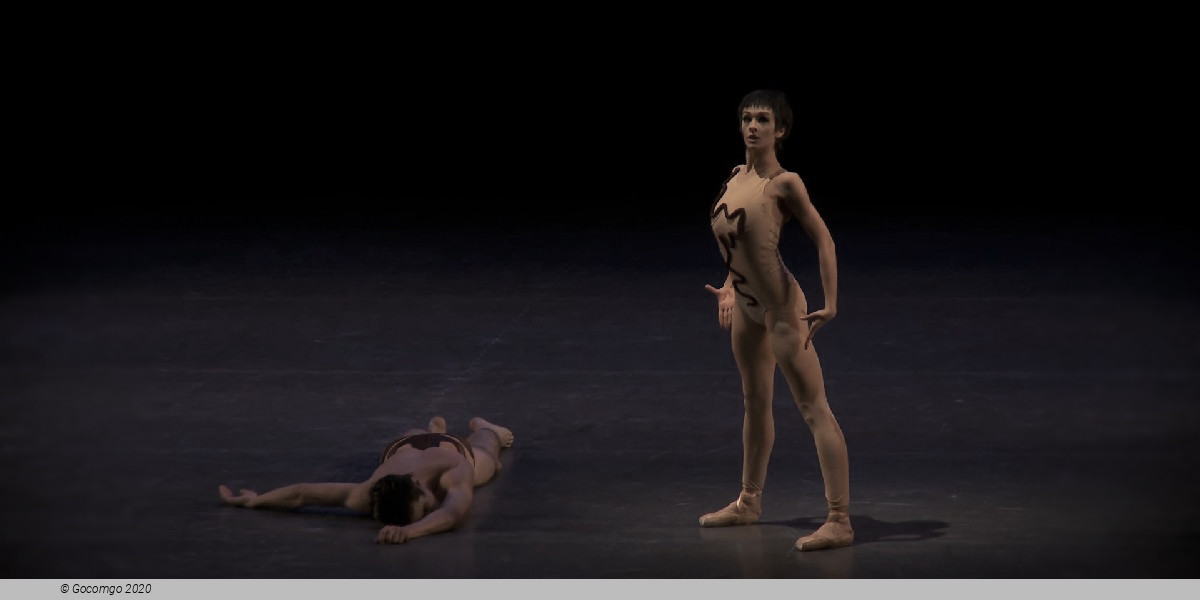

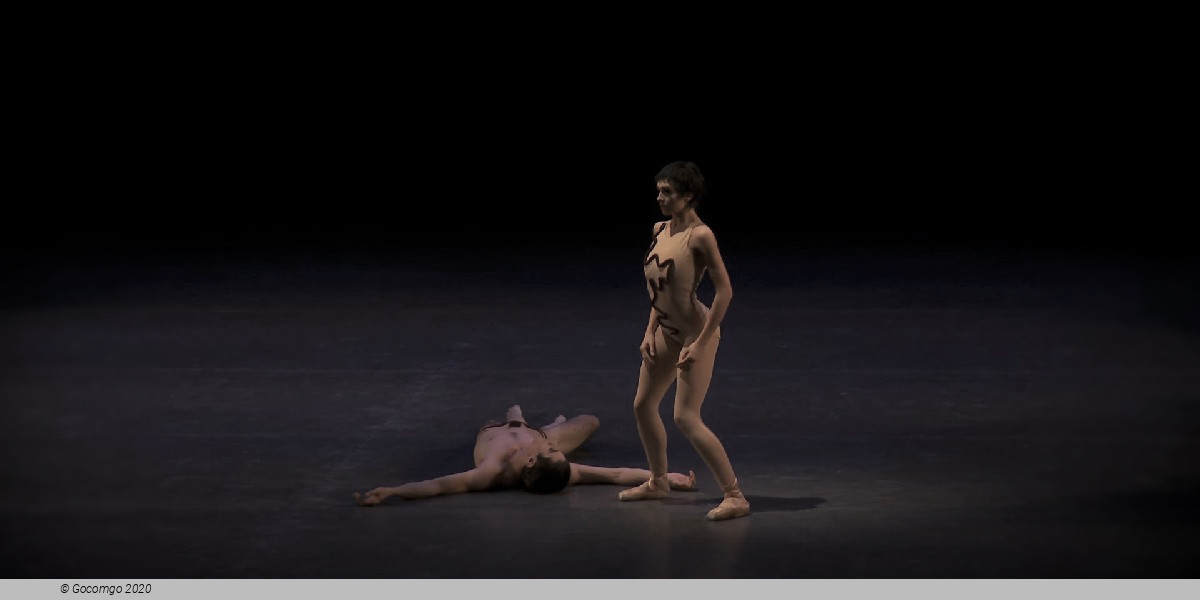

The Cage plunges into the world of natural selection, using Stravinsky’s daring score to depict the feral instinct compelling the female of an insect species to consider its male counterpart as prey.

Stravinsky composed his Concerto in D for String Orchestra in 1946, as a commission for the 20th anniversary of the Basler Orchestra; it was his first work for string orchestra since Apollon Musagète. The vivid, haunting composition features a shift between D major and minor throughout the work and a rich quality for the writing of the strings. Jerome Robbins used Stravinksy’s concerto for one of his early works, The Cage, which imagines a community of female creatures. In describing the ballet, Robbins said, “I did not have to confine myself to human beings moving in a way that we know is human. In the way their fingers worked, in the crouch of a body or the thrust of an arm, I could let myself see what I wanted to imagine.”

An animated dance for a neoclassical couple, the dancers periodically stop and listen to the onstage musicians before ending with a poignant scene in a pool of light on a dark stage.

Stravinsky dedicated Duo Concertant to Samuel Dushkin, a well-known violinist he met in 1931. The composer premiered the work with Dushkin in Berlin in 1932, and the pair gave recitals together across Europe for the next several years. Balanchine first heard the piece performed by Stravinsky and Dushkin soon after it was composed, but not until years later, when he was planning the 1972 Stravinsky Festival, did he decide to choreograph it.

Balanchine long admired Duo Concertant and finally choreographed the score as a pas de deux for New York City Ballet’s historic 1972 Stravinsky Festival. Nancy Reynolds, Director of Research for The George Balanchine Foundation, writes, “Duo Concertant was seen as the essence of what the festival was all about: it was not only a close union of dance with music, dancers with musicians (pianist and violinist were on the stage); here, the music actually penetrated the dancing, and did not merely accompany it: the dancers stood still at times and visibly listened. And in its intimacy, the ballet recalled the very personal nature of the fifty-year collaboration that the festival both celebrated and prolonged.”

The ballet was made on New York City Ballet principal dancers Kay Mazzo and Peter Martins. Mazzo has written: “Lincoln Kirstein called Duo Concertant ‘a little jewel,’ and Jerome Robbins said at the premiere that he was amazed Mr. B had the nerve to have the dancers just listen to the music for the whole first movement. Mr. B said, ‘Aha, dear, that’s the point of all dancing. You must first listen to the music and really hear, and then you will understand it and appreciate it. You see the music in the steps, but first you must hear the music!’ I believe Mr. B was very proud of this beautiful ballet and felt he was really delivering the message that he firmly believed. At the end of the ballet, he said to me that it showed that ballet to him was woman, that she was on a pedestal and that was how he wanted his women to be.”

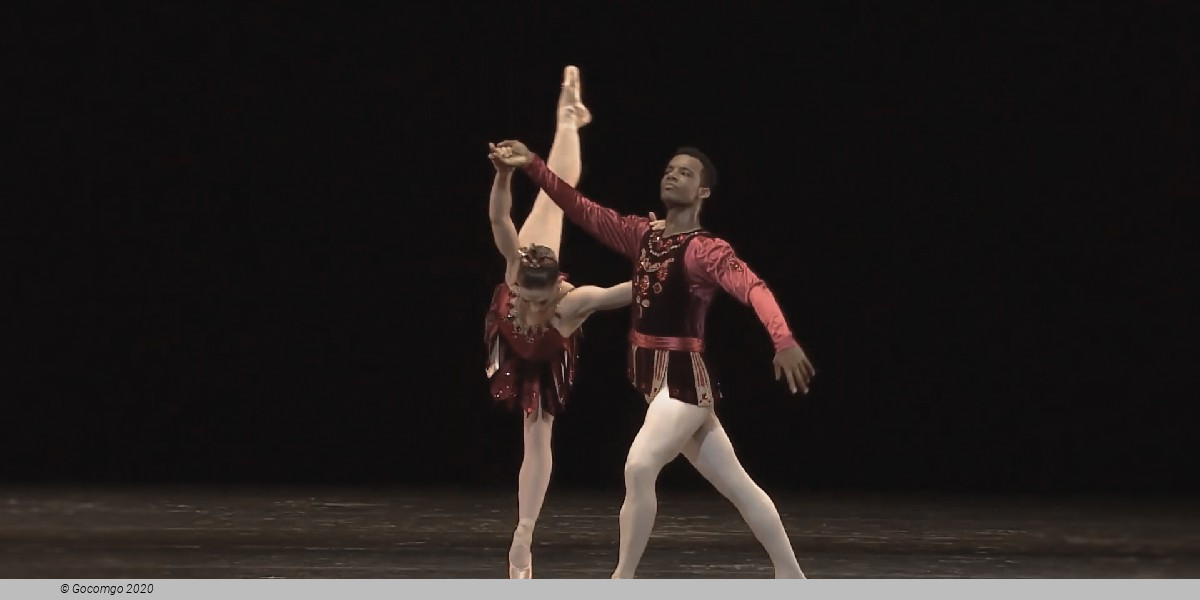

Rubies sends its dancers racing across the stage like lightning to Stravinsky’s jazz-inflected piano capriccio, emphasized by a sharp attack and sassy style.

Igor Stravinsky composed his three-movement Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra, the music for Rubies, in 1928-29. He intended it as a vehicle for his own appearances as a concert pianist and as something of a relief from his Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments, which he had written five years before for the same purpose. The Capriccio is, in effect, a second piano concerto. Stravinsky said that as he wrote this score he had in mind Carl Maria von Weber, a composer he championed; in fact, he quotes Weber in the music. Another of Stravinsky’s enthusiasms that affects the Capriccio is the cimbalom. Figurations typical of this east European instrument are in evidence at various places in the solo piano part — in certain repeated notes and in the cadenza in the second movement, for example. Balanchine set the second movement as a pas de deux for the principal dancers, and they and a soloist dance with the corps de ballet in various combinations in the outer movements.

20 Lincoln Center Plaza

20 Lincoln Center Plaza