Essential works from the visionary mind of NYCB’s founding choreographer.

Three celebrated works from Balanchine evoke intriguingly contrasting atmospheres. In Rubies, from the full-length ballet Jewels, the jazz-inflected score sets the stage for a romp glinting with wit, surprise, and thrilling choreography. The Four Temperaments, a repertory favorite throughout the Company’s history, is a plotless neoclassical work loosely inspired by the ancient belief that human behavior is defined by four elements, or “humors”: the melancholic, the sanguinic, the phlegmatic, and the choleric. The mysterious La Valsedepicts a young woman dancing with increasing abandon under the influence of an enigmatic figure enticing her to the edge of darkness.

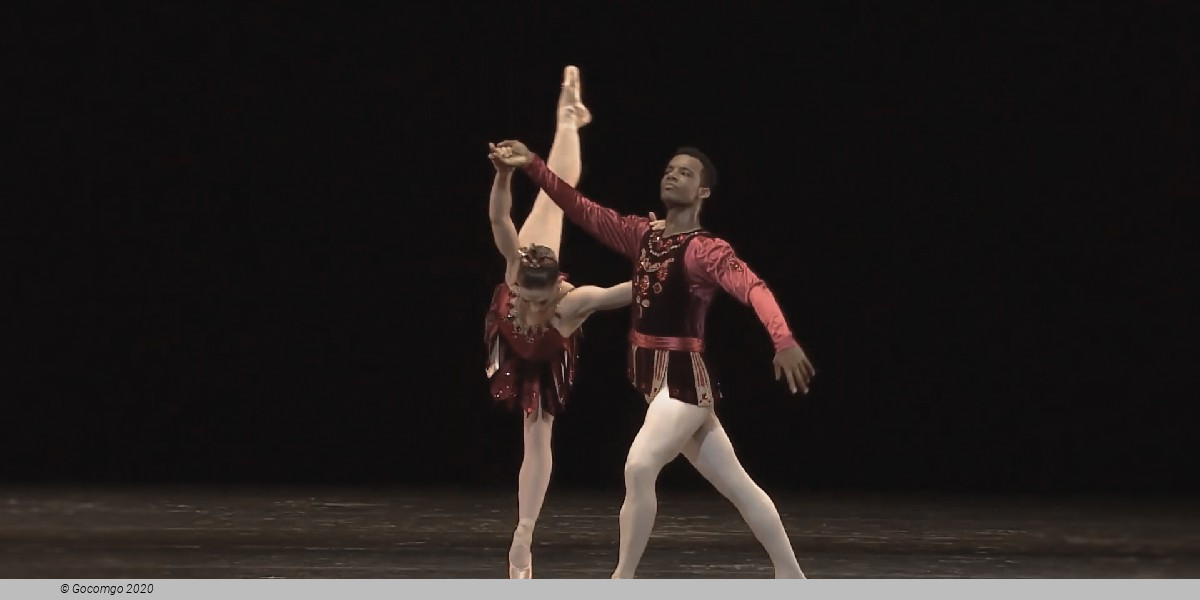

Rubies sends its dancers racing across the stage like lightning to Stravinsky’s jazz-inflected piano capriccio, emphasized by a sharp attack and sassy style.

Igor Stravinsky composed his three-movement Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra, the music for Rubies, in 1928-29. He intended it as a vehicle for his own appearances as a concert pianist and as something of a relief from his Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments, which he had written five years before for the same purpose. The Capriccio is, in effect, a second piano concerto. Stravinsky said that as he wrote this score he had in mind Carl Maria von Weber, a composer he championed; in fact, he quotes Weber in the music. Another of Stravinsky’s enthusiasms that affects the Capriccio is the cimbalom. Figurations typical of this east European instrument are in evidence at various places in the solo piano part — in certain repeated notes and in the cadenza in the second movement, for example. Balanchine set the second movement as a pas de deux for the principal dancers, and they and a soloist dance with the corps de ballet in various combinations in the outer movements.

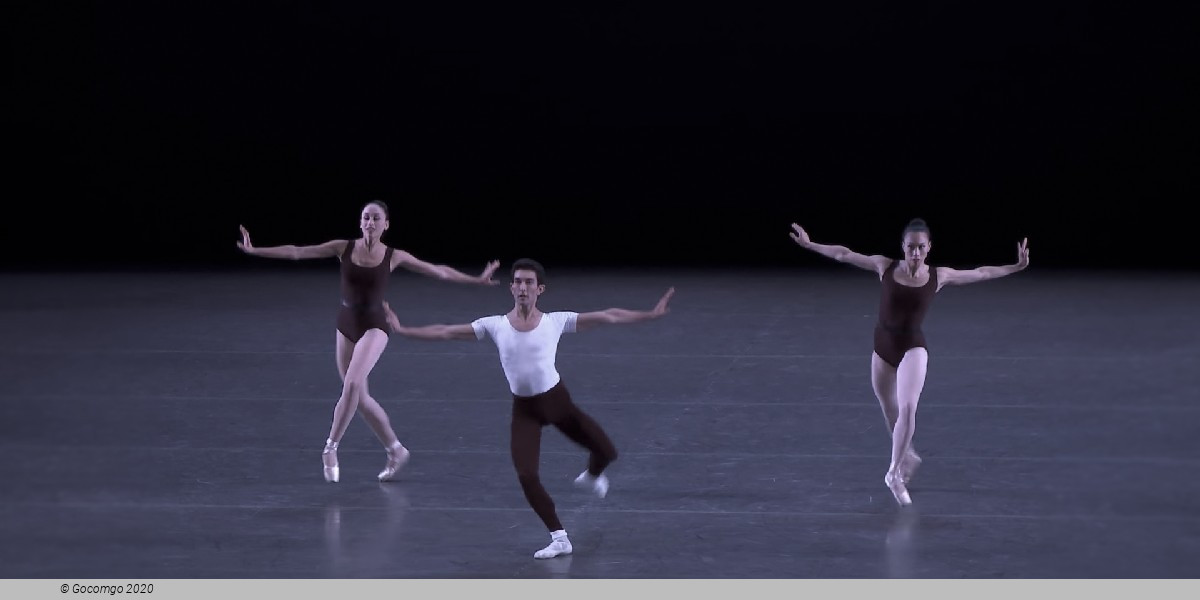

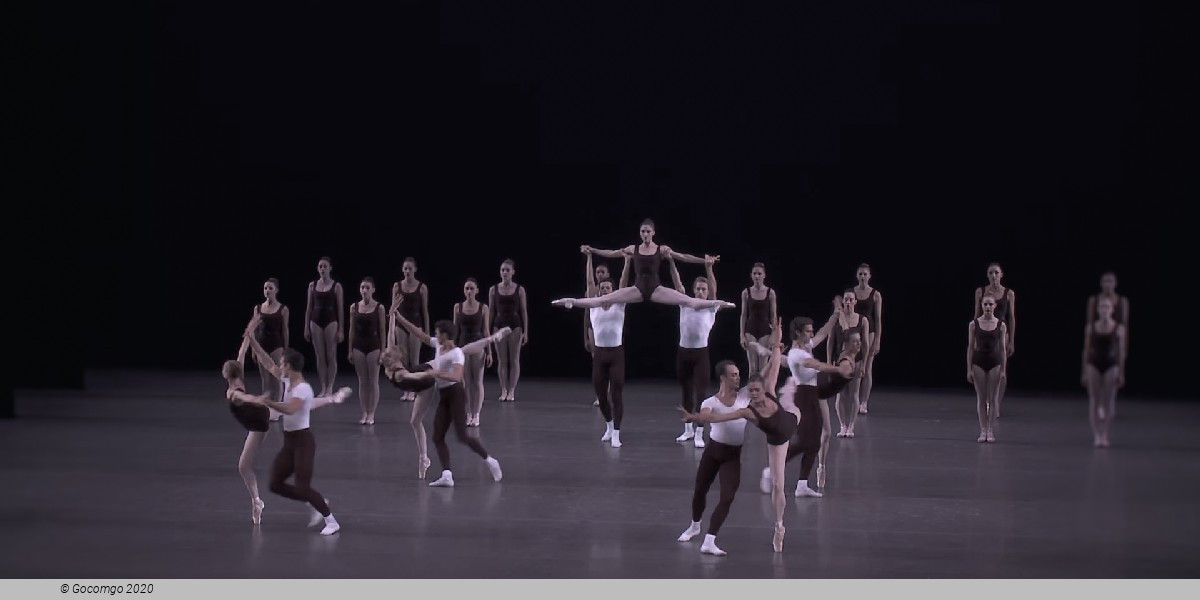

A ballet with unceasing appeal, The Four Temperaments references the medieval concept of psychological humors through its classically grounded but definitively modern movement.

The score for this ballet was commissioned by George Balanchine from Paul Hindemith in 1940. The ballet, together with Ravel’s opera L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, constituted the opening program of Ballet Society (the direct predecessor of the New York City Ballet) on November 20, 1946. In Complete Stories of the Great Ballets, Balanchine wrote of the ballet that it “is an expression in dance and music of the ancient notion that the human organism is made up of four different humors, or temperaments. Each one of us possesses these four humors, but in different degrees, and it is from the dominance of one of them that the four physical and psychological types — melancholic, sanguinic, phlegmatic, and choleric — were derived …. Although the score is based on this idea of the four temperaments, neither the music nor the ballet itself makes specific or literal interpretation of the idea. An understanding of the Greek and medieval notion of the temperaments was merely the point of departure for both composer and choreographer.”

An accomplished pianist, Balanchine commissioned the score because he wanted a short work he could play at home with friends during his evening musicales. It was completed in 1940 and had its first public performance at a 1944 concert with Lukas Foss as the pianist.

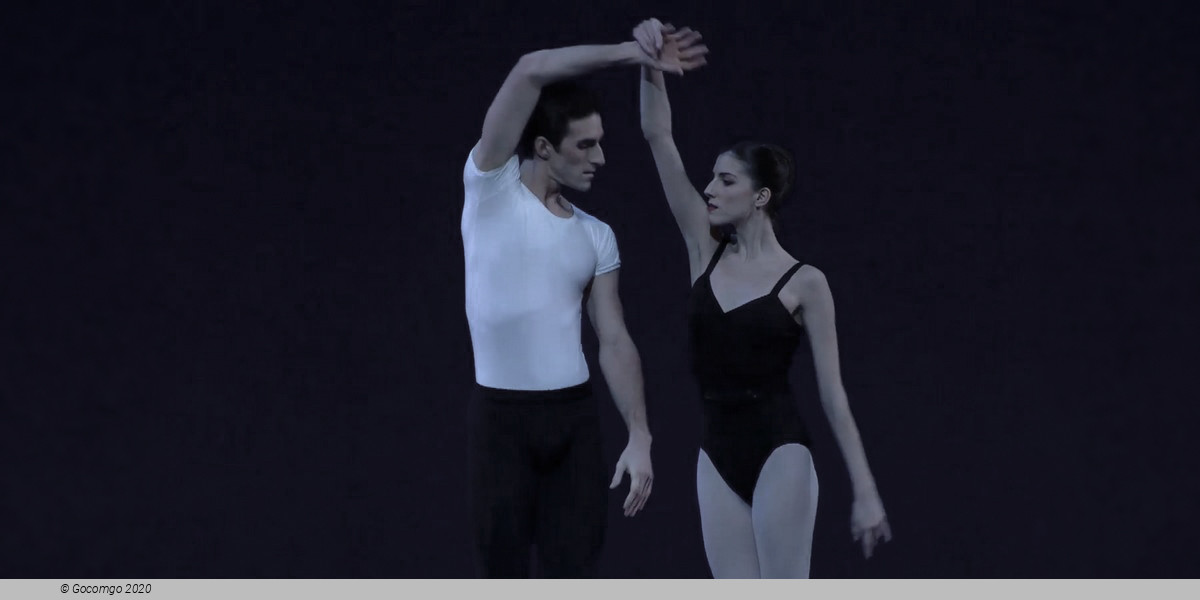

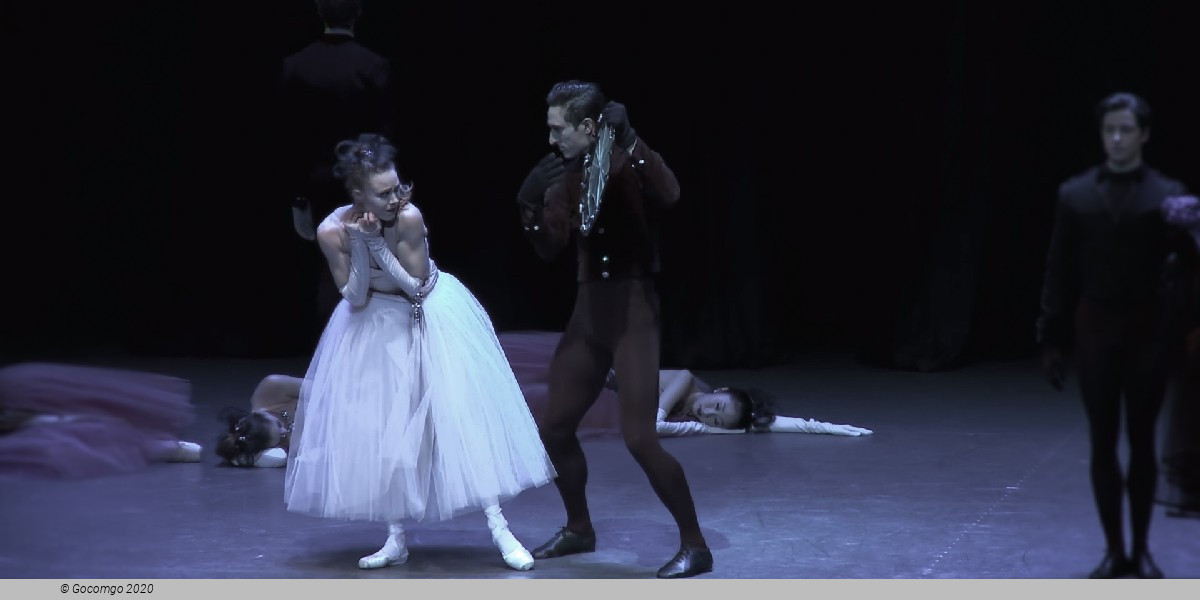

Captivated by the moody and mysterious world of Ravel’s La Valse, a young woman waltzes through Balanchine’s surging choreography with tragic results.

"We are dancing on the edge of a volcano," Maurice Ravel wrote in his notes to La Valse. His words are an apt description of both the music and Balanchine's neo-romantic choreography: couples waltzing in a cavernous ballroom where a woman in white is at once horrified and fascinated by the uninvited figure of death.

Intrigued by the disintegration of the waltz form, Ravel envisioned La Valse set in the Imperial Court of Vienna in 1855, and called the score "a choreographic poem … a sort of apotheosis of the Viennese waltz … the mad whirl of some fantastic and fateful carousel."

Serge Diaghilev commissioned the score for his Ballets Russes, but rejected it for being "untheatrical." When Balanchine created La Valse in 1951, he found the score to be too short and preceded it with Ravel's Valse Nobles et Sentimentales, eight short waltzes, which establish the mood of the ballet — a mood of superficial gaiety mixed with an uncertain feeling of impending catastrophe.

20 Lincoln Center Plaza

20 Lincoln Center Plaza