Refinement and style meet in four canonical Balanchine and Robbins works

An enticingly varied program comprises essential works from the Company’s founding choreographers. The program opens with Balanchine’s Divertimento No. 15, the rare ballet he composed to a work by Mozart and a glittering display of pure classicism that has remained a favorite of both audiences and dancers. From Robbins comes his bewitching pas de deux Afternoon of a Faun, considered one of his greatest achievements despite its simplicity, followed by two more by Balanchine: Le Tombeau de Couperin, a neoclassical ballet steeped in elegance and courtly refinement, and The Four Temperaments, an exemplar of the neoclassical style Balanchine defined with his Black & White ballets.

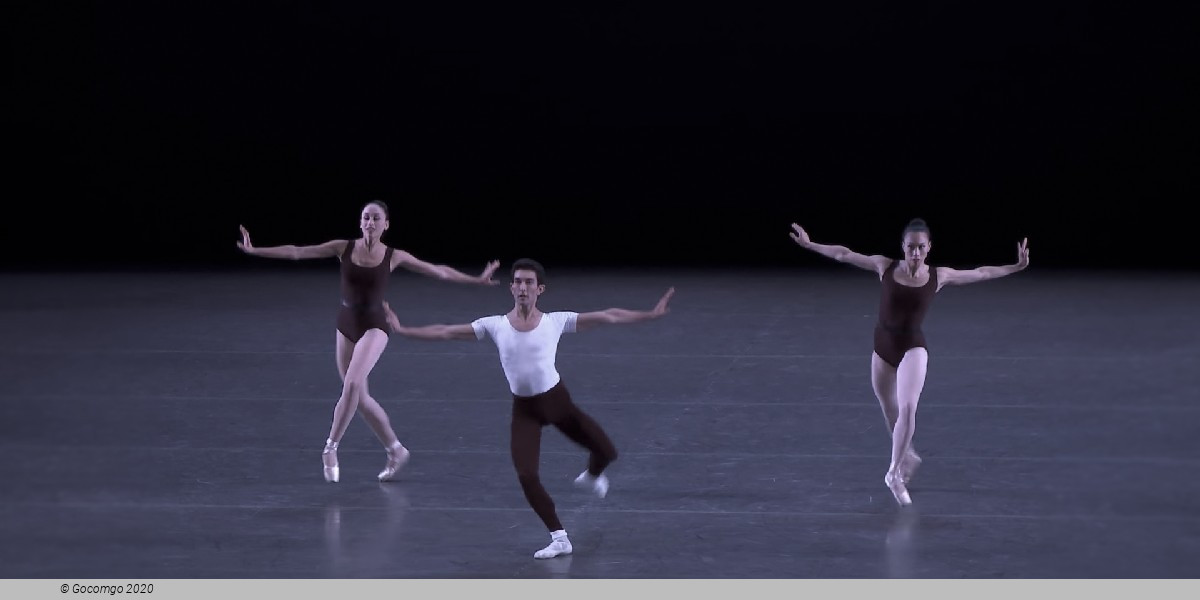

Balanchine considered Mozart’s Divertimento No. 15 the finest ever written, and to compliment the sparkling score, he created a work of prodigious ingenuity featuring a regal cast of dancers.

When asked to present a work at the Mozart Festival held at the American Shakespeare Theater in Stratford, Connecticut, in 1956, Balanchine originally planned to revive Caracole, an earlier work set to Mozart’s Divertimento No. 15. Instead, he created a new ballet that used many steps from the old, and he named the new ballet after the music, which he considered the finest divertimento ever written. The divertimento genre reached its zenith amid the parties and informal entertainments of 18th-century aristocratic life. Divertimentos did not have a fixed structure; the number of movements could vary from one to twelve, and they could be scored for one instrument or a chamber orchestra. Divertimento No. 15 is choreographed for eight principal dancers, five women and three men, with an ensemble of eight women. The ballet omits the second minuet and the andante from the sixth movement; a new cadenza for violin and viola by John Colman was added in the late 1960s.

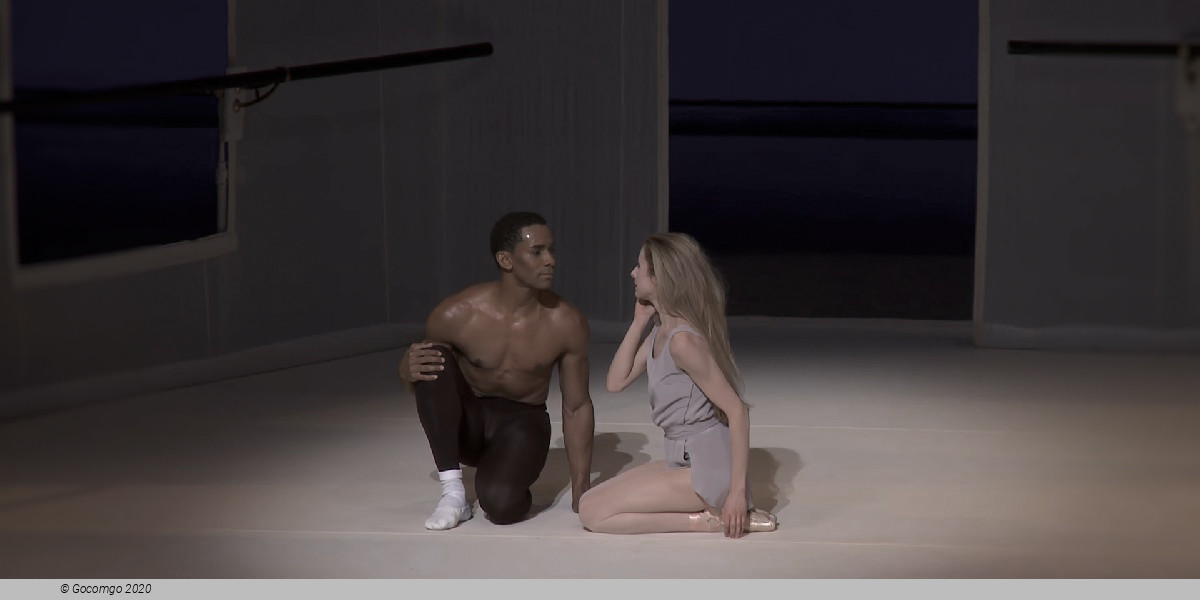

Subtle, sensual, and narcissistic, Afternoon of a Faun depicts a chance encounter between two young dancers in a studio.

Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune was composed between 1892 and 1894. It was inspired by a poem by Mallarmé that was begun in 1865, supposedly for the stage; the final version appeared in 1876. The poem describes the reveries of a faun around a real or imagined encounter with nymphs. In 1912 Nijinsky presented his famous ballet, drawing his ideas from both the music and the poem, among other sources, including Greek sculpture and painting. This pas de deux, choreographed by Jerome Robbins, is a variation on these themes. It was first performed in 1953 by New York City Ballet, and is dedicated to Tanaquil Le Clercq, for whom the ballet was choreographed.

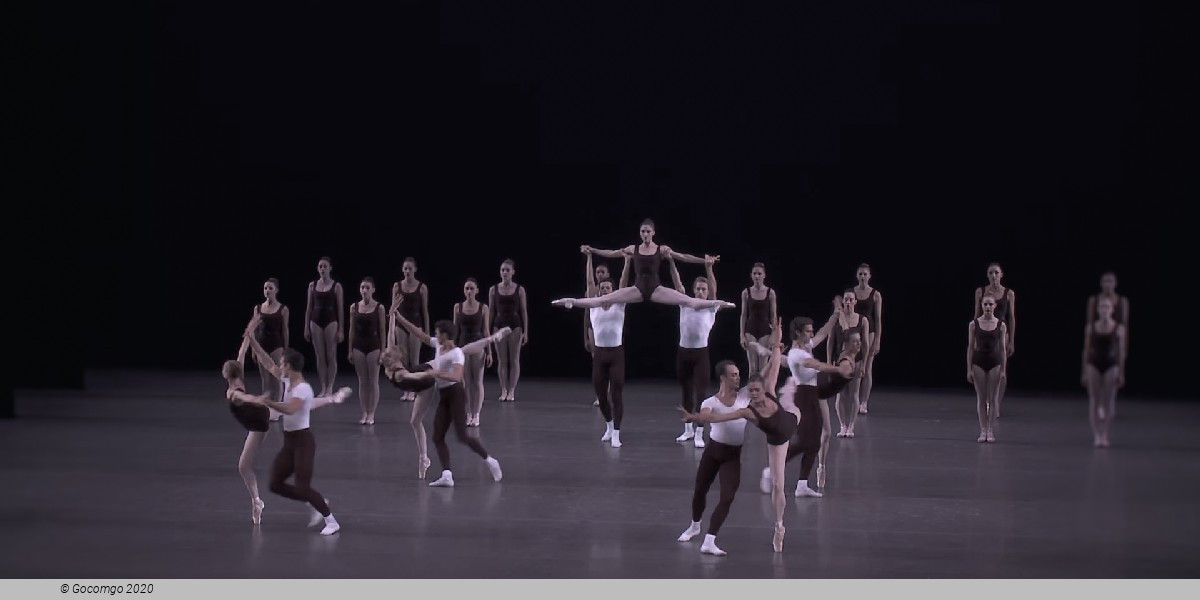

Rooted in the court dances of 18th-century France, Le Tombeau de Couperin mesmerizes with its seamless patterns and symmetrical groupings of dancers.

In 1919 Maurice Ravel composed "Le Tombeau de Couperin” (“The Tomb of Couperin”), a commemorative suite for piano in six movements, in memory of six friends who died in World War I. He was inspired by the style of François Couperin, a French Baroque composer. In 1920, Ravel orchestrated four of the pieces, which make up the score for this ballet.

Balanchine choreographed Le Tombeau de Couperin for New York City Ballet’s 1975 Ravel Festival, and, like the composer, he incorporated French Baroque style and devices into a work with a modern sensibility. The eight couples are divided into left and right quadrilles, and each quadrille forms geometric patterns — diagonals, diamonds, squares — as they dance in unison or echo the movements of the opposite side.

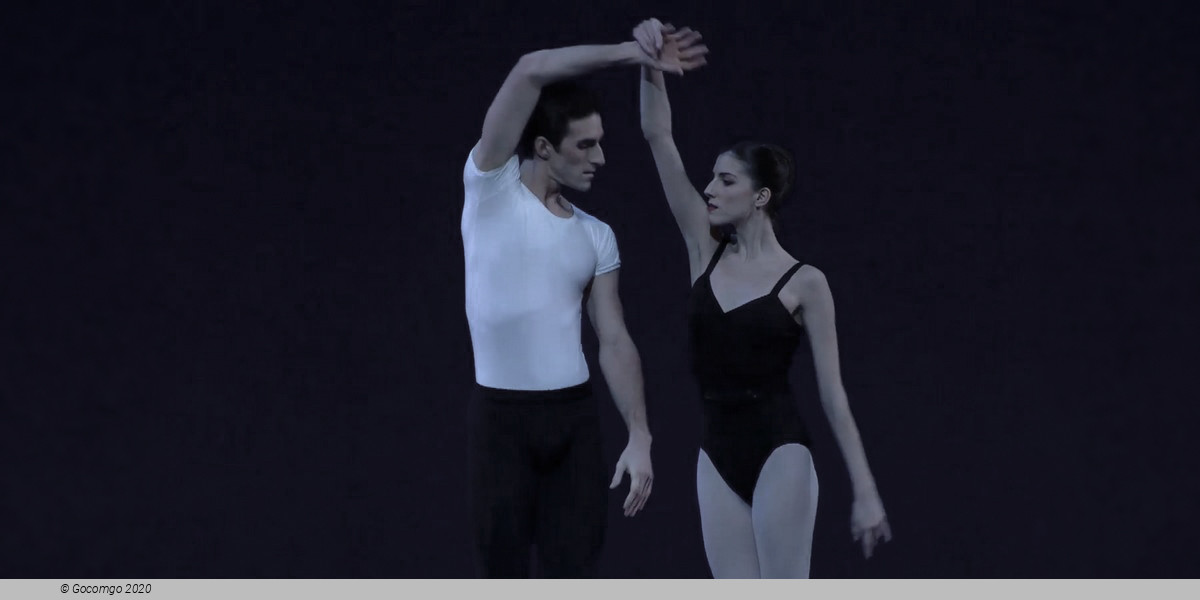

A ballet with unceasing appeal, The Four Temperaments references the medieval concept of psychological humors through its classically grounded but definitively modern movement.

The score for this ballet was commissioned by George Balanchine from Paul Hindemith in 1940. The ballet, together with Ravel’s opera L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, constituted the opening program of Ballet Society (the direct predecessor of the New York City Ballet) on November 20, 1946. In Complete Stories of the Great Ballets, Balanchine wrote of the ballet that it “is an expression in dance and music of the ancient notion that the human organism is made up of four different humors, or temperaments. Each one of us possesses these four humors, but in different degrees, and it is from the dominance of one of them that the four physical and psychological types — melancholic, sanguinic, phlegmatic, and choleric — were derived …. Although the score is based on this idea of the four temperaments, neither the music nor the ballet itself makes specific or literal interpretation of the idea. An understanding of the Greek and medieval notion of the temperaments was merely the point of departure for both composer and choreographer.”

An accomplished pianist, Balanchine commissioned the score because he wanted a short work he could play at home with friends during his evening musicales. It was completed in 1940 and had its first public performance at a 1944 concert with Lukas Foss as the pianist.

20 Lincoln Center Plaza

20 Lincoln Center Plaza