Music from three centuries illustrates the breadth of Balanchine’s tastes. The classic Concerto Barocco brings together the pristine beauty of Bach’s music with Balanchine’s own lush but spare neoclassical choreography. The 20th-century modernist Paul Hindemith provided the music for Kammermusik No. 2, a frisky dance featuring a rare all-male corps supporting two principal couples. And while waltzes were composed as early as the 16th Century, the dance in three-quarter time reached its apogee in 19th-century Vienna, inspiring Balanchine’s intoxicating celebration of its heyday.

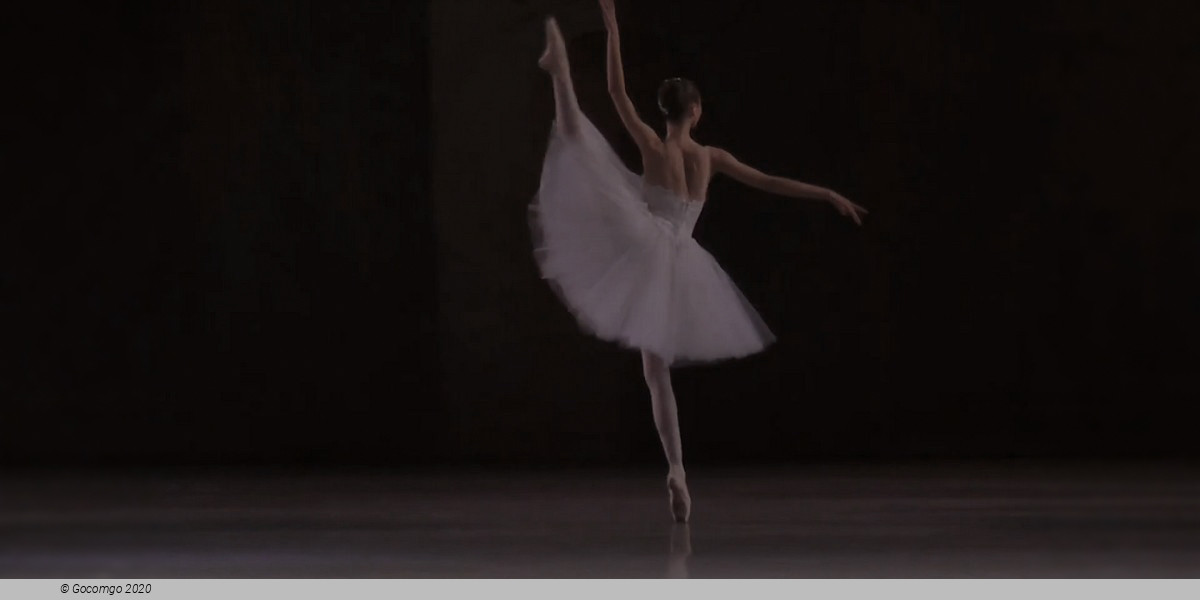

One of Balanchine’s greatest masterpieces, Concerto Barocco is music made visible as two elegant yet dynamic lead ballerinas each depict one of the instrumental soloists in a virtuosic double violin concerto.

Concerto Barocco had its beginnings as a School of American Ballet exercise and was first performed for the Latin American tour of the American Ballet Caravan in 1941. When it entered the repertory of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1945, the dancers were dressed in practice clothes, probably the first appearance of what has come to be regarded as the modern ballet costume pioneered by Balanchine.

Concerto Barocco was presented on the first performance of New York City Ballet in 1948, along with Balanchine's Orpheus and Symphony in C. It is considered the quintessential Balanchine ballet of its period, its manner entirely pure, its choreography no more, and no less, than an ideal response to its score, Bach's Double Violin Concerto in D Minor. About the ballet, the critic Clive Barnes wrote, "The three hallmarks of the American classic style are poetry, athleticism, and musicality, and these three graces are exquisitely exploited by Concerto Barocco."

Balanchine said of this work: “If the dance designer sees in the development of classical dancing a counterpart in the development of music and has studied them both, he will derive continual inspiration from great scores.” In the first movement of the concerto, the two ballerinas personify the violins, while a corps of eight women accompany them.

In the second movement, a largo, the male dancer joins the leading woman in a pas de deux. In the concluding allegro section, the entire ensemble expresses the syncopation and rhythmic vitality of Bach’s music.

Requiring great energy, speed, and precision, the striking choreography in Kammermusik No. 2 echoes the intricacies of its modernist score with jagged lines and stylized gestures.

A ballet requiring great energy, speed, and precision, Kammermusik No. 2 has a complex structure that echoes the music; one of the dancers in the original cast likened it to a computer. The ballet is performed by two couples and an eight-man ensemble. The men, with their jagged lines and stylized gestures, dance to the music of the orchestra. The soloists, dancing to the complex passages for piano, are in counterpoint to the ensemble. The score is one of seven kammermusik pieces — the word “kammermusik” is German for “chamber music” — written by Hindemith between 1923 and 1933, when the composer turned to a neoclassical style evoking the Baroque.

A work of monumental scale with a magnificent finale, the five-part Vienna Waltzes is set in moonlit Austrian forests and the regal ballrooms of Vienna.

The waltz, which became popular in the late 1700s, was a dance form Balanchine revisited and explored often over his career, but never on as grand a scale as he did for the 1977 Vienna Waltzes. Through Rouben Ter-Arutunian’s evolving scenery, the ballet—Balanchine’s homage to an age of imperial grandeur—transforms from a sylvan forest glen to a dance hall to a glittering society café to, at last, a majestic mirrored ballroom. The music for each section of the ballet is associated with the gradual transformation of the waltz across society. The many elaborate costumes are the last that Barbara Karinska, NYCB’s principal costume-maker for many years and Balanchine’s longtime collaborator, created for New York City Ballet.

20 Lincoln Center Plaza

20 Lincoln Center Plaza