Igor Stravinsky’s music, which has become an intrinsic element of New York City Ballet’s repertory, serves as the compelling force for four contrasting favorites from Balanchine and Robbins.

Russian composer Igor Stravinsky’s personal and professional relationship with George Balanchine constituted one of the great artistic partnerships of the 20th Century. On this program, two Balanchine ballets are paired with two created by Jerome Robbins, also an ardent admirer of the composer. Apollo, Balanchine’s first major collaboration with Stravinsky, dates to 1928 and is the oldest dance in the repertory; by contrast, Symphony in Three Movements, a classic leotard ballet, was created more than 40 years later, in a distinctly different style. Robbins is represented by The Cage, an intense and enjoyably macabre dance about fierce female creatures, and Concertino, a more rarely seen pas de trois drawn from a larger work.

Balanchine's first collaboration with Stravinsky and one of his earliest international successes, Apollo presents the young god as he is ushered into adulthood by the muses of poetry, mime, and dance.

"Apollo I look back on as the turning point of my life. In its discipline and restraint, in its sustained oneness of tone and feeling, the score was a revelation. It seemed to tell me that I could dare not to use everything, that I, too, could eliminate."

George Balanchine

Apollo is the oldest Balanchine ballet in New York City Ballet’s repertory. Created for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and originally titled Apollon Musagète, the ballet premiered in Paris in 1928 and was Balanchine’s first major collaboration with composer Igor Stravinsky. With this dramatic and powerful ballet, which created a sensation when it was first performed, the 24-year-old Balanchine achieved international recognition. The 1928 premiere of the ballet featured sets and costumes by the French painter André Bauchant and in 1929 new costumes were created by Coco Chanel. The ballet was first performed by New York City Ballet in 1951, and during his lifetime Balanchine continued to revise the work, eliminating sets, costumes, and much of the ballet’s narrative content.y Ballet revival, actor Jack Noseworthy served as the narrator.

Scenery and costumes for Balanchine's production were by French artist André Bauchant. Coco Chanel provided new costumes in 1929. Apollo wore a reworked toga with a diagonal cut, a belt, and laced up. The Muses wore a traditional tutus. The decoration was baroque: two large sets, with some rocks and Apollo's chariot. In the dance a certain academicism resurfaced in the stretching out and upward leaping of the body, but the Balanchine bent the angles of the arms and hands to define instead the genre of neoclassical ballet.

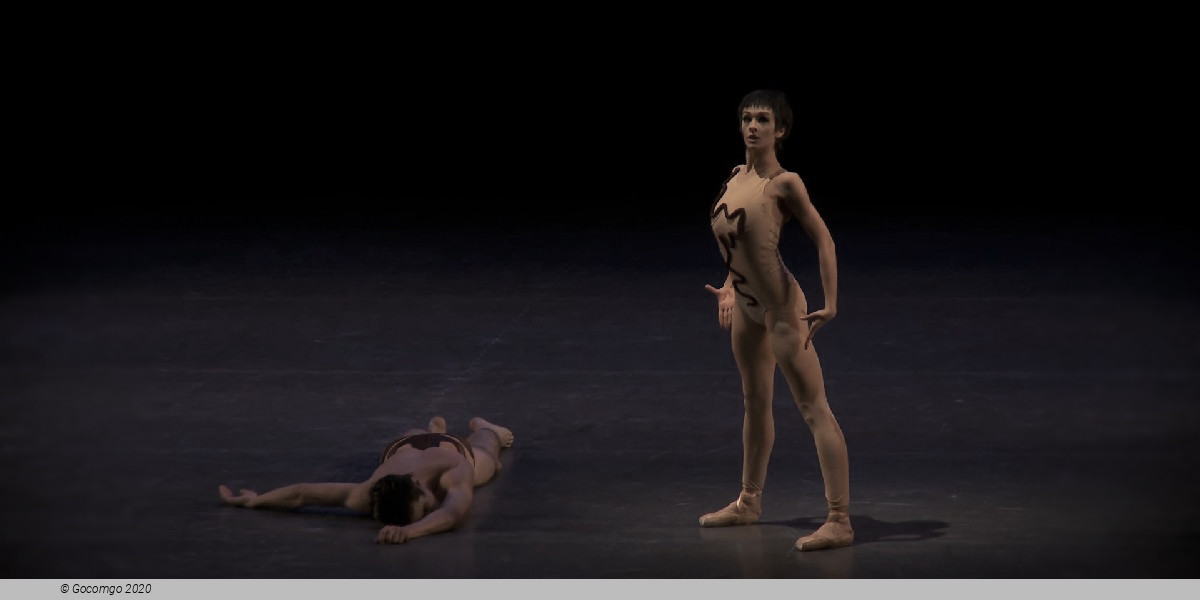

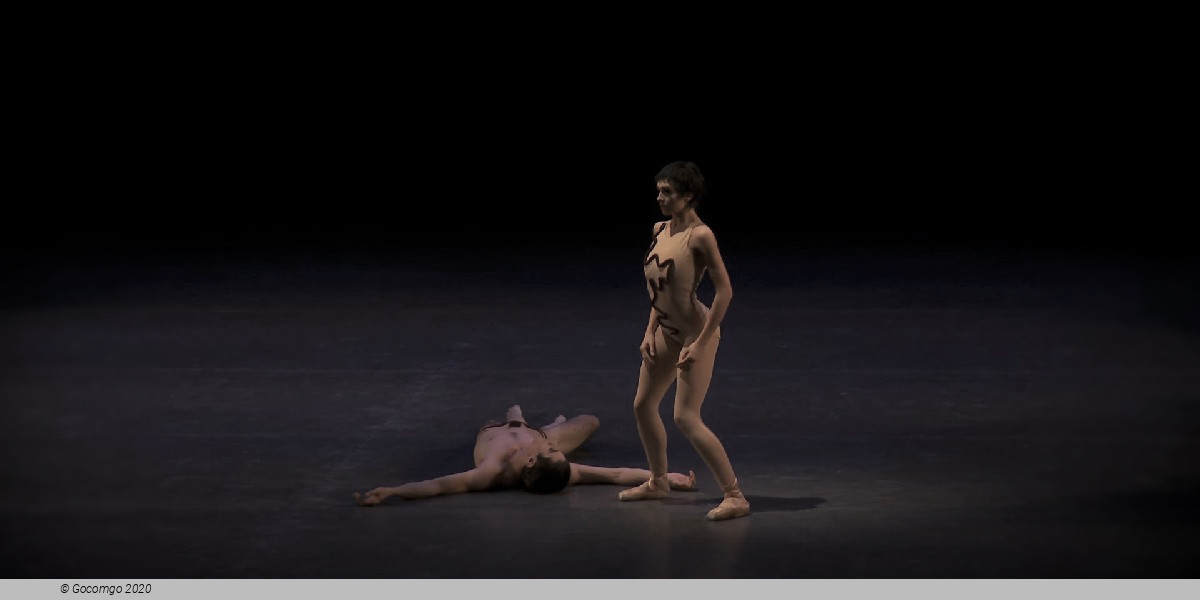

The Cage plunges into the world of natural selection, using Stravinsky’s daring score to depict the feral instinct compelling the female of an insect species to consider its male counterpart as prey.

Stravinsky composed his Concerto in D for String Orchestra in 1946, as a commission for the 20th anniversary of the Basler Orchestra; it was his first work for string orchestra since Apollon Musagète. The vivid, haunting composition features a shift between D major and minor throughout the work and a rich quality for the writing of the strings. Jerome Robbins used Stravinksy’s concerto for one of his early works, The Cage, which imagines a community of female creatures. In describing the ballet, Robbins said, “I did not have to confine myself to human beings moving in a way that we know is human. In the way their fingers worked, in the crouch of a body or the thrust of an arm, I could let myself see what I wanted to imagine.”

The captivating suspense of Stravinsky’s score, at times swelling, at others intricately layered, accompanies a trio of dancers and their compelling connectivity.

Robbins choreographed a ballet titled Four Chamber Works for the 1982 Stravinsky Centennial celebration. Five unrelated chamber works were incorporated into a four-part ballet; the third section, Concertino, choreographed to two of these pieces of music, is now performed separately.

One of Balanchine’s most celebrated leotard ballets, Symphony in Three Movements is bold and breathtakingly jet-propelled, a kinetic achievement, striking for its confidence and power.

For New York City Ballet’s 1972 Stravinsky Festival, Balanchine choreographed several notable masterpieces, including the majestic Symphony in Three Movements. Stravinsky had suggested the music as a ballet when the choreographer visited the composer in Hollywood during World War II. Despite its 21 minute length, the piece evokes a fuller symphonic breadth with two instruments, the harp and piano, providing the dominant contrasts. “Each instrument has a large obbligato role in a movement to itself, and only at the turning- point fugue…do the two play together and unaccompanied,” said Stravinsky. The signature Stravinsky propulsive rhythm is mirrored by the angular, athletic choreography for soloists and a large ensemble, although the second andante movement, originally composed for an apparition scene in the movie Song of Bernadette, is reserved for a meditative pas de deux. One of Balanchine’s “leotard” ballets, the work requires no scenic or narrative distractions from the complexity of the choreography.

It was during his tenure at the legendary Ballets Russes, from 1924 until the death of Serge Diaghilev in 1929, that Balanchine met Igor Stravinsky, marking the start of a long-time artistic partnership between two kindred spirits. Balanchine's Symphony in Three Movements was created for the Stravinsky Festival in 1972. With sporty and athletic elements, this snappy, snazzy ballet is a testament to Balanchine’s pioneering spirit and exceptional musicality.

20 Lincoln Center Plaza

20 Lincoln Center Plaza